Born in 1619, Charles Le Brun was a French artist, court painter of Louis XIV, decorator of the Versailles palace, and director of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.

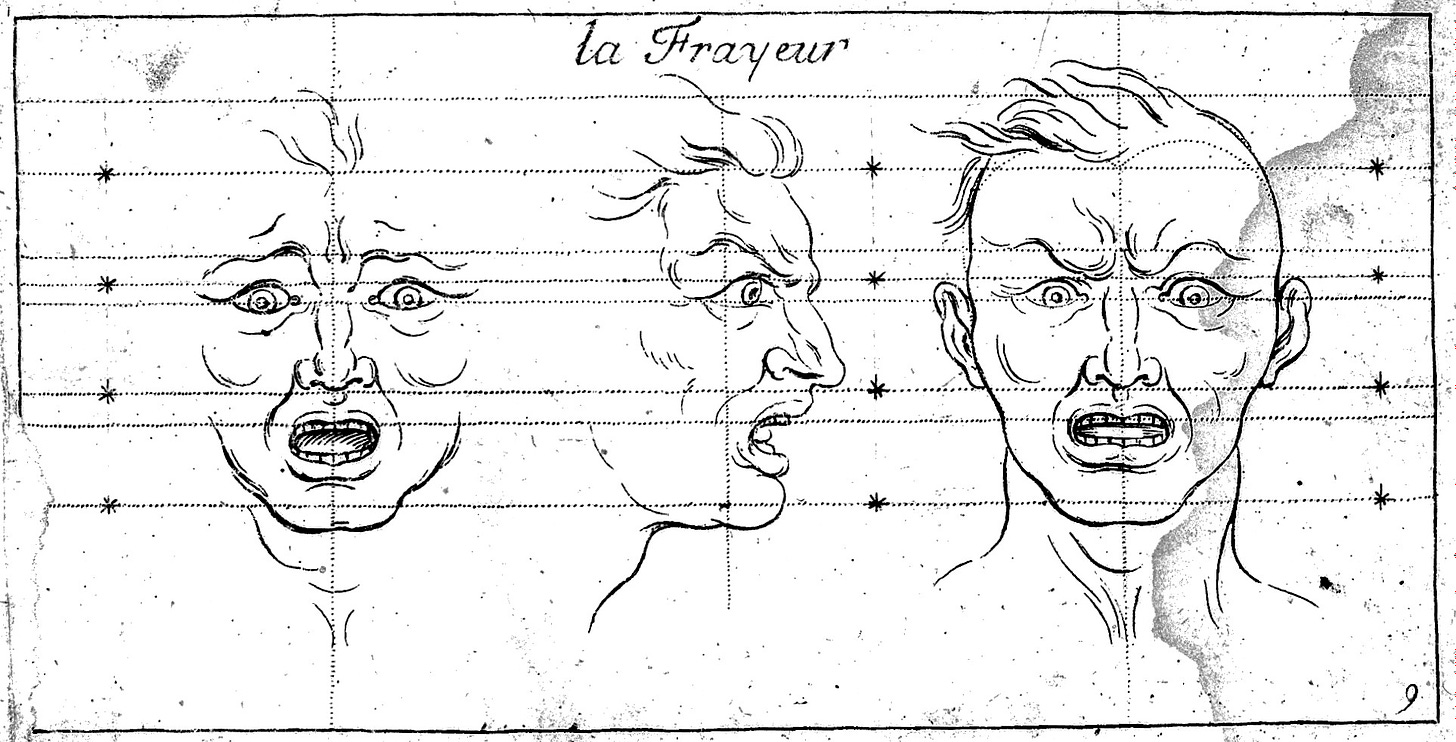

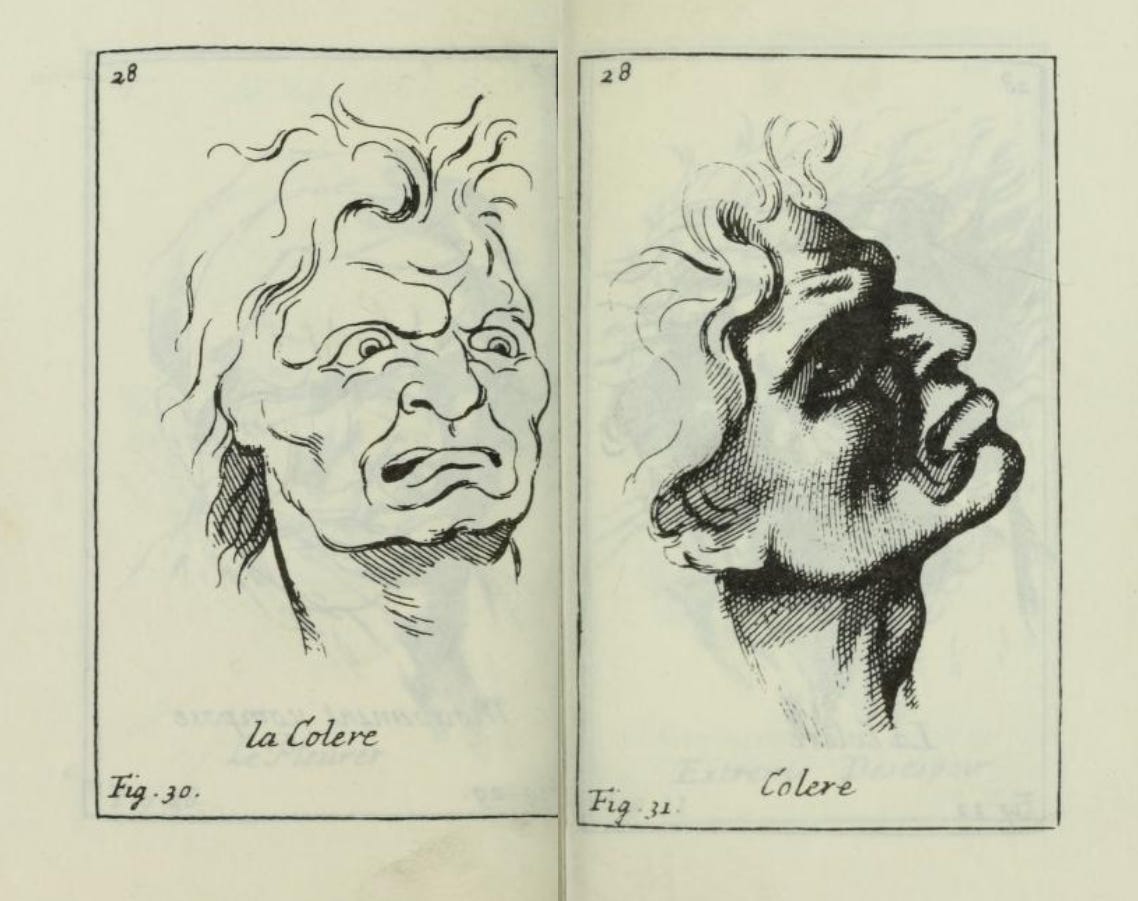

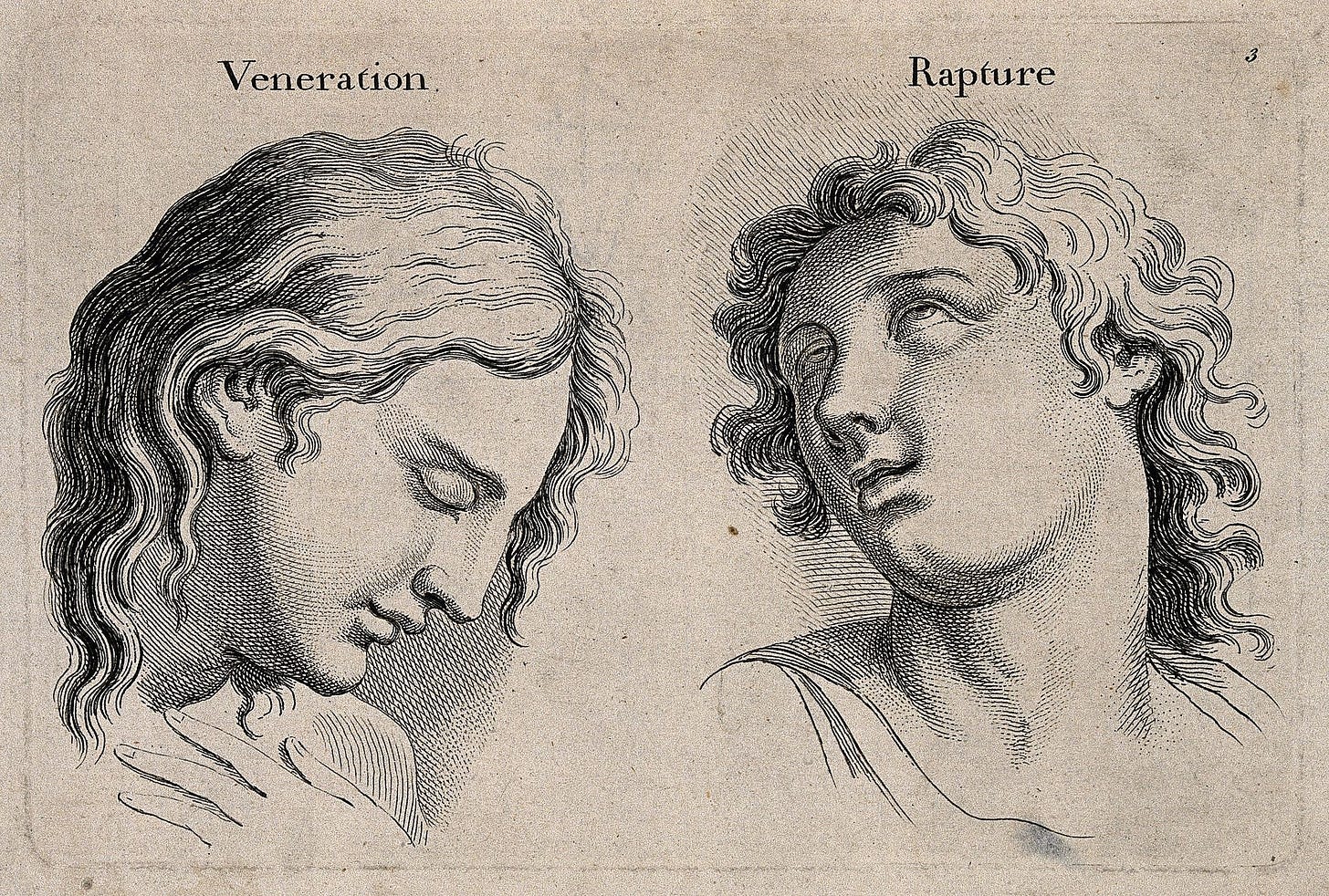

In 1668 Le Brun gave a series of lectures, titled “Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions.” Or, a method for learning to draw the passions. In it, Le Brun explained how the artist can express the passions in his art. Through detailed descriptions of the visual characteristics accompanying the various passions man can experience, the artist could be better guided in his work.

In Xenophon’s Memorabilia, we read about a conversation between Socrates and the painter Parrasius, renowned for his life-like works of art. Socrates asks the artist:

"Do you imitate a most persuasive, pleasing, loving, longed-for, and passionately beloved thing, the soul's character? Or is this not a thing that can be imitated?"

Parrasius answers: "How could a thing be imitated, Socrates, which has neither proportion nor color nor any of the things you just now mentioned and which is altogether unseen?”

Indeed, how could an artist, who necessarily works with visible materials, imitate the soul, which is strictly speaking invisible? But Socrates is not satisfied with the answer, and he asks Parrasius if the soul’s character doesn’t show itself in how a person carries himself, in his deeds, in his facial expressions, etc. And indeed, it does. And these things through which the soul’s character shows itself, these can be imitated by the artist. Parrasius is forced to agree. The artist might not be able to depict the soul directly, but he can express the character of the soul through the various ways in which it shows itself —the expressions on someone’s face, his deeds, the health of his body, and so on.

It is this idea, that the soul can be expressed in art through the various ways in which it shows itself in the visible body, that will guide Le Brun’s treatise. We can say that Le Brun wrote a treatise on how to express the soul in art. He says: “I want to show you how bodily expression shows the movements of the soul, which render visible the effects of the passions.”

Interestingly, Le Brun was inspired by the philosopher René Descartes, especially the latter’s text ‘The Passions of the Soul’. In this text, Descartes gives an explanation of the passions, how they come about, and what their function is.

What is a passion for Descartes? In short, a passion is everything the soul undergoes; “those perceptions, sensations or emotions of the soul which we refer particularly to it, and which are caused, maintained and strengthened by some movement of the spirits.”

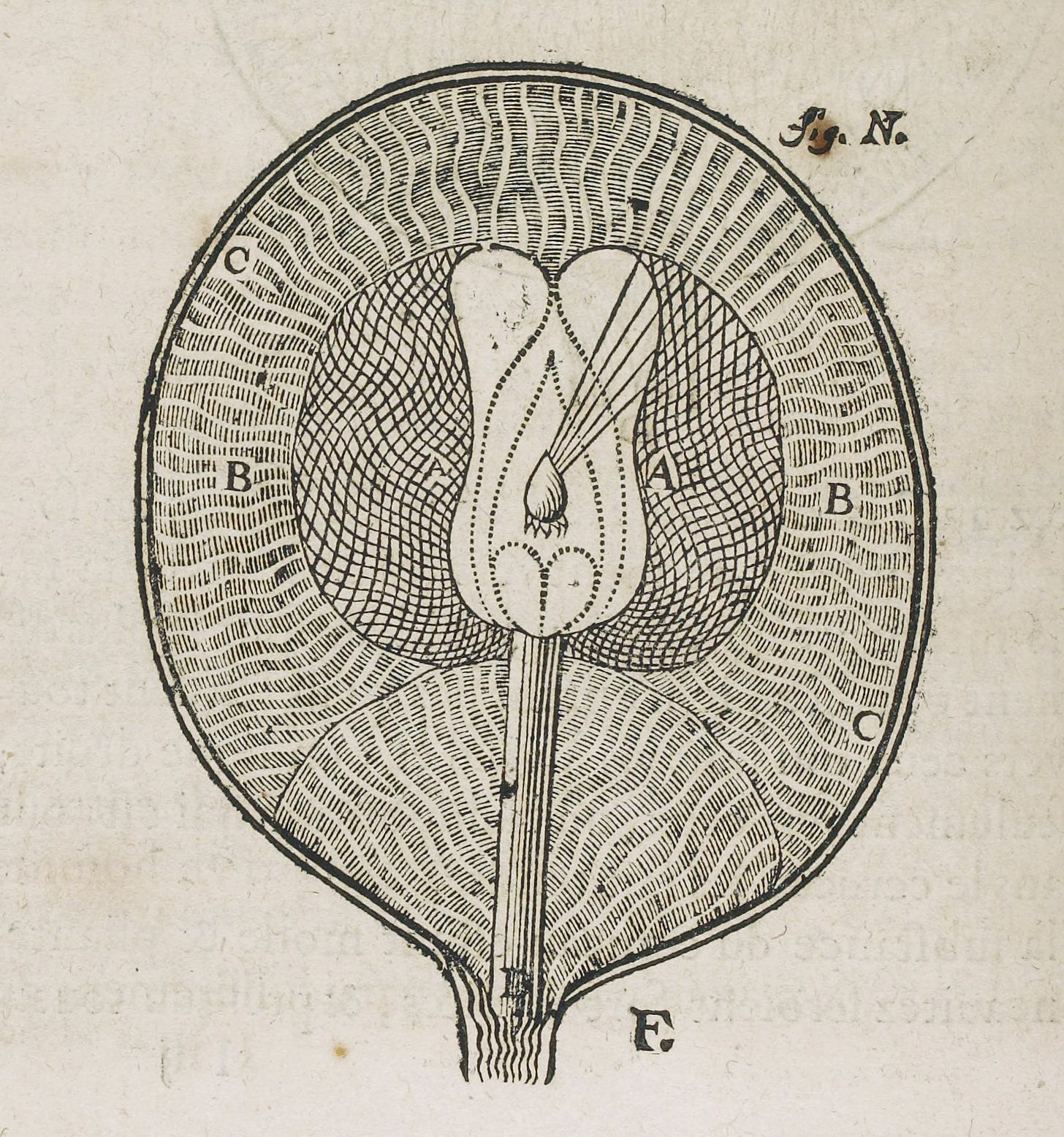

These spirits, ‘esprits animaux’, are animating principles of motion in the body, they stimulate the muscles, organs, and brain, and thus cause the body’s movements. For example, someone hits me with a stick on my arm, my nerves register the hit and animal spirits are sent to my brain, I feel pain and rage perhaps (passions), and animal spirits again flood into my body from my brain, inciting me to jump away perhaps or return a hit.

The movements in the body explain the passions, but in turn, the passions of the soul incite movement in the body. What is important is that Descartes is here trying to give an entirely mechanistic explanation of the passions. He wants to explain them by referring to the physiology of the body and the movements that occur in it, and nothing else.

Every passion we experience, every movement of the soul, has a corresponding movement in the body. And thus, every passion we experience internally, must be visible in the body. In his lectures, Le Brun states too that “everything that causes passion in the soul, causes a certain movement in the body.” This is important.

If even the most internal and invisible things a soul can experience — the passions (love, hate, wonder, sadness, etc.,) —, make themselves visible in the body, then the artist can express these things in his painting. Nothing of the human experience remains un-representable.

It is clear that Le Brun is interested in physiognomy, the art of assessing the character of a person’s soul on the basis of his appearance, especially the appearance of the visage. And for Le Brun, this art becomes essential to the art of painting.

In an important passage, applying his characteristic method of doubt to the passions, Descartes says that we can doubt the objects to which the passions refer, but we cannot doubt that a passion is truly in the soul. For example, if I dream of being chased by someone in a dream, and I feel fear because of it. I can doubt that I was actually being chased, for it was a dream. And I can doubt that I thus feared something. But that I felt fear, I cannot doubt this.

“Thus often when we sleep, and sometimes even when we are awake, we imagine certain things so vividly that we think we see them before us, or feel them in our body, although they are not there at all. But even if we are asleep and dreaming, we cannot feel sad, or moved by any other passion, unless the soul truly has this passion within it.”

Thus, the passions truly tell us something about our soul. I can doubt all the objects that my soul puts its attention to, but the passions, these are absolutely certain, and these truly give us an impression of what it means to be a soul.

We know Descartes most of all from a different proof; ‘I think, (therefore) I am’. It is interesting that in The Passions of the Soul he gives us this certainty of the passions. The passions are what happen to the soul, what the soul undergoes. But thought, the soul does not undergo this, rather, it is the one sole activity of the soul. Interestingly, Descartes has thus given us two different proofs of what is truly to be attributed to the soul; one from the perspective of action (thought), and another from the standpoint of suffering (passions).

I can doubt everything I think about, but I cannot doubt that I think. And I can doubt the reality of everything that ignites a passion in me, but that I truly feel passion, this I cannot doubt. Whatever it might mean to exist, we know that it means action, and we know that it means suffering.

The passions truly tells us something about the depths of our soul, and hence, there is no greater task for the artist, than to express the passions of the soul. And the expressions on our bodies tell us something about our souls, as all internal dispositions of the soul are a reflection of the outward movements of the body, and vice-versa. Thus, the artist must express those visible counterparts of the internal dispositions of the soul.

And, if we can make a precise inventory of all the various passions and their corresponding bodily movements, will this not lead to better art? In the same way that a knowledge of all the various colours can aid the artist? This is the vision of Le Brun.

In Le Brun’s treatise, he often adopts Descartes’ descriptions of the passions quite literally, and ads his own notes on how the artist can best express these passions. Concerning wonder (l’admiration) for example, we read in Descartes: “Wonder is a sudden surprise of the soul which brings it to consider with attention the objects that seem to it unusual and extraordinary.” And in Le Brun, we read: “wonder is a surprise which makes the soul consider with attention the objects which appear to it as strange and extraordinary.”

The question of influence is complex, some say Le Brun sought to adopt Descartes’ theory entirely, others say he distorted it or made significant changes to it. What is certain is that here we have an interesting example of a philosopher and a painter living in the same period who had similar concerns. In philosophy, Descartes sought to make a complete theory of the passions, and categorise them in a clear manner. So that the reader could better control his own passions. And in art, Le Brun sought to give models for how to paint the passions, categorising them in a clear manner, so that other painters could make use of them, and be more precise in their painting.

With Descartes, the passions, the most illusive of aspects of the human experience, perhaps more aptly expressed in literature, become an object for rational ordering in philosophy, and find their explanation in the movements of the body. And likewise with Le Brun, the passions can be expressed by following precise rules of composition.

The 17th century is the age of reason, and both Le Brun and Descartes give us insight into what this might have meant.

Even the most ‘irrational’ aspects of the human experience become a subject for rational inquiry. Reason is unchained, and it will conquer the world.

Does this conquering of the passions by reason make the passions less valuable? Not at all, if we must listen to Descartes and Le Brun. Rather, by gaining scientific knowledge of them, we can express them to even greater degrees. In The Passions of the Soul, Descartes says that "persons whom the passions can move most deeply are capable of enjoying the sweetest pleasures in this life." But, the passions may also cause the most bitterness for those who do not know how to order them and put them to good use. And hence, Descartes' project; to order the passions, so that we can make good use of them.

"The chief use of wisdom lies in its teaching us to be masters of our passions and to control them with such skill that the evils which they cause are quite bearable, and even become a source of joy." -Descartes

Sources:

Descartes. The Philosophical Writings: Volume I. Translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, Dugald Murdoch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Descartes. The Philosophical Writings: Volume II. Translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, Dugald Murdoch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Charles Le Brun. Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions: proposée dans une conférence sur l'expression générale et particulière. Georg Olms Verlag: 1982.

Xenophon. Memorabilia. Translated by Amy L. Bonnette. Cornell University Press: 1994.