“The best choose one thing in exchange for all, everflowing fame among mortals; but most men have sated themselves like cattle.”

(Heraclitus, XCVII (D.29, M.95))

I. Introduction: swine and men

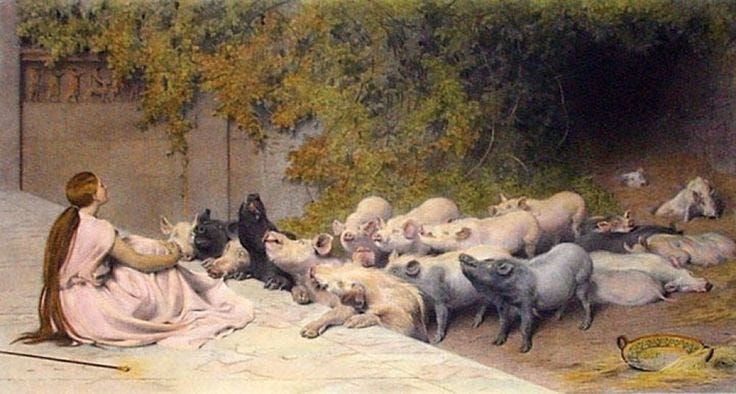

In Ancient Greek thought, the lowest of men are often referred to as ‘swine’. Swine are animals which have their ‘values’ opposed to the values of men. Men value cleanliness, but swine desire to bathe in filth, to “root and roll in mud”, as Homer says. (Homer, Odyssey, X 269) A man wants to accomplish goals set by reason, a pig only seeks the immediate gratification of its desires: eating, drinking, fucking, and sleeping. You might think that this is not much different from your own desires at times. And this is precisely why the idea has such an importance for the Greeks. We are men, but if we do not watch out, and blindly follow our desires, we will end up living like pigs. Not much different from Odysseus’ men, who are turned into swine by Circe in the Odyssey.

The worst among men have their values upside down, they like what ought to be disliked, they prefer filth over what has worth, and hence, they are pigs. They are guided only by sense pleasure, entirely incapable of having their actions guided by reason. They cannot be trusted, their values are twisted, and their reason is corrupted by their senses.

Heraclitus speaks:

“swine delight in mire more than clean water.”

(Heraclitus, LXXII (D.13 M. 36))

What distinguishes man from other animals is his capacity for reason. Man is the reasonable animal, it is said. Human beings can rise above instinct and pleasure, and can understand things, pursue moral standards, and, through action, actualize ideals set by reason. All these things distinguish us from animals and plants. But if, as a man, you do not choose to rise above instinct and pleasure, and you do not choose to understand things or hold yourself to moral standards. If you are not intent on actualizing any ideals, except for the immediate gratification of your desires, then are you really a man? What makes you different from an animal? If none of the things that characterize man are applicable to you, but all of the things that characterize swine are applicable to you? Then why would we still call you a man, and not a pig?

In Ancient Greek thought, there is this idea of a choice, of either pursuing the good in becoming like a man, or pursuing evil in becoming like a pig. The dynamic of this choice, which expresses the entirety of man’s moral predicament, is what I want to speak about today. I will do so by explaining this dynamic of choice, using Plotinus and some key passages from Heraclitus and Plato. And I will illustrate this dynamic by looking at Odysseus’ confrontation with Circe in Homer’s Odyssey.

II. They will lie in Hades

As our starting point, we take a passage from Plotinus:

“For it is indeed the case, as the ancient doctrine has it, that self-control and courage and every virtue is a purification and is wisdom itself. For this reason, the mysteries correctly offer the enigmatic saying that one who has not been purified will lie in Hades in slime, because one who is not pure likes slime due to his wickedness. They are actually like pigs that, with unclean bodies, delight in such a thing.”

(Plotinus, Enneads, I.6.6.)

In this passage, Plotinus refers to two sayings. One you recognize already, Heraclitus’ saying that “swine delight in mire more than clean water.” The impure like what is to be disliked, just like a pig doesn’t like to be clean, but delights in filth. The pig is thus a great metaphor for the transformation that happens in wickedness, whereby all that is evil comes to be desired as good, and all that is good comes to be rejected as if it were evil. The person that we are influences the opinions that we hold, the sights that we put our attention to, and the dialectical reasonings we undertake. It is thus of great importance to ‘stay clean’, so that our desires and our thoughts remain clean and trustworthy too. There might be such a thing as pure reason, but only for those who are able to keep themselves pure. This is what is expressed in Heraclitus’ fragment. And hence the importance of philosophy, the practice of seeing truth clearly, which is inseparable from living according to truth. For if we don’t live in accordance with truth, we turn into pigs. In which case, we will not be able to see the truth clearly.

Plotinus also refers to Plato’s Phaedo when he speaks of “the ancient doctrine.” In the Phaedo we read that moderation, courage, justice, and wisdom serve the ends of purification. And it is said:

“that whoever arrives in the underworld uninitiated and unsanctified will wallow in the mire, whereas he who arrives there purified and initiated will dwell with the gods.”

(Plato, Phaedo, 69c)

Those who wallow in the mire are those who arrive in the underworld uninitiated and unsanctified. And who likes to wallow in the mire? Precisely, pigs, as Heraclitus told us. The pigs are those men who are uninitiated and unsanctified, and the unsanctified are pigs. What does it mean to be unsanctified or wicked, what is this evil of being a pig? And what is its contrary, what does it mean to be a man? I will explain by way of Plotinus.

In Plotinus’ system, man’s soul emanates from the Divine One, and descends from this One into the world of matter. In this sense man is an amphibian being, one part of his soul is connected to the divine, and one part of his soul is connected to matter. Plotinus thus speaks of both a rational and an irrational part of the soul. The rational part being connected to Being and to the One, the irrational part being connected to non-being and matter. The rational part consists of man’s capacity for reason, that which separates him from other animals. Whereas the irrational part consists of our senses and bodily urges and desires. Our task as a human soul is to become more of ourselves, to actualize our essence. And our essence is that of a reasonable animal. That is, we must, as an animal connected to both the divine and the sensible world, actualize that which makes us uniquely ourselves: reason. As men, we must follow what makes us men: reason. In this way we strengthen our connection to ourselves and the Divine, and we weaken our connection to matter. Failing to do so, and only following our irrational part, is failing to be fully ourselves, failing to be fully human. This means that in our interactions with matter through the senses, we should let these interactions be guided by our rational part.

Very concretely, my urge could be to eat a certain food, but by reason I know this food to be harmful for my health. And thus, following reason means not listening to my urge, but listening to reason instead. I might feel the urge to harm someone, but I know that it is not good to do so. You must think of it in this very concrete sense. To let reason and truth guide our actions, and not our mere sensible urges. To do this more and more, and in this way live a life more and more in accordance with reason, this is what it means to become purified as in Plato’s fragment. But what happens when we don’t do this, and we renounce listening to our rational soul, living a life entirely guided by our irrational soul? We become pigs. Why? We are present here, as a soul —both rational and irrational—, and something in the sensible world attracts our attention. A certain food or drink presents itself to us, and ignites in us the desire to consume it. But we know well, by reason, that it is better not to consume this food or drink for our health. Yet, we do so anyways. We listen to our irrational part, and renounce listening to our rational part. Having listened to this urge once, we strengthen the force by which this urge speaks to us, and the sound of reason’s command grows dimmer. We now have not only the urge pulling us in the direction of the food or the drink, but also the actual pleasure of the food or drink. The urge has now grown stronger, it has more force behind it. Having accepted the urge once, it becomes easier to do it a second time, and harder to refrain from it. And if we continue listening to the senses, it becomes like a habit, or an addiction. And now, being addicted, the command of reason sounds dimmer and dimmer, until it is barely audible at all. At first, we consciously give our attention over to the urges of the senses, and consciously go ahead with their proposed action. But after a while, this process becomes entirely unconscious, and we lose touch with our own power over the senses. We become less like men, and more like animals. Blindly following our bodily urges, never following reason. Only listening to the senses, and never listening to reason. And like an addict will shut out all information that makes him face the harm of his addiction, the addict to matter will shut out the voice of reason. Having failed to listen to his rational essence, and being silently conscious of this ‘sin’, he will turn away from his essence more and more. Fleeing himself, further into the addiction. Becoming less of a man, and more of an animal. All to not have to face the judgement that comes from within. Heraclitus says that

“Eyes and ears are poor witnesses for men if they have barbarian souls.”

(Heraclitus, XVI. (D. 107, M.13))

Those whose souls are corrupted by matter, those who have become ‘pigs’, are not to be trusted. For they will twist the truth so as to uphold their addiction. And they will not listen to the truth, for facing the truth would mean facing their own wickedness.

This is the basic dynamic of souls, as seen in Plotinus, but common to Plato, Aristotle, and most of the thinkers we deem characteristic of Greek thought. We either become more of ourselves by following reason, or we lose ourselves by fleeing into matter. We become men by acting as men, or we become like swine, by acting as swine. A beautiful illustration of this process is given in Homer’s Odyssey, when Odysseus and his men come in contact with the enchantress Circe.

III. Deceived away from home.

The Odyssey tells the tale of Odysseus and his men who seek to return to their home —Ithaka—, after having fought many years in the Trojan war. The journey home is supposed to be smooth, but fate has it that Odysseus must face many obstacles along the way, many obstacles that seek to prevent him from reaching home, and many obstacles that seek to deceive him in to renouncing his conviction to get home. One of these obstacles is given by Circe. When Odysseus’ ship reaches the island of Aeaea, where Circe resides, he sends his men inland to scout the island. Circe is known as an enchantress, capable of deceiving anyone, and turning men into wolves, lions, and swine by the help of all sorts of potions and herbs.

When the men go into the island they come across Circe’s palace. The palace is surrounded by wolves and lions, but curiously, these beasts do not attack the men. Rather, they calmly yet eagerly come to roam around them, as a dog or a cat might come to its master when it returns home. The men go closer to the palace and hear someone inside singing an enthralling song. The men are curious, when Polites, the man in command, decides that they should call out to whoever it is that is singing. And so they call out, and Circe opens the doors of her palace, inviting the men inside. But one man, Eurylochus, stays behind. He senses that something is wrong, that danger looms, and he decides to stay outside. What happens next?

“She ushered them in to sit on high-backed chairs, then she mixed them a potion —cheese, barley and pale honey mulled in Pramnian wine— but into the brew she stirred her wicked drugs to wipe from their memories any thought of home. Once they’d drained the bowls she filled, suddenly she struck with her wand, drove them into her pigsties, all of them bristling into swine —with grunts, snouts—even their bodies, yes, and only the men’s minds stayed steadfast as before. So off they went to their pens, sobbing, squealing as Circe flung them acorns, cornel nuts and mast, common fodder for hogs that root and roll in mud.”

(Homer, Odyssey, X 250-270)

With her potions, Circe has turned the men into swine. The story unfolds with Eurylochus returning to Odysseus, telling him of what has happened. Odysseus then goes to Circe to save his men, but becomes deceived himself, until eventually —after a year of living in the enchantress’ deception— they get out safe and well, the men being turned back into men, and everyone remembering that they need to get home to Ithaka. I am here not interested in this further enfolding of the story, but merely in the basic dynamic of Circe’s deception which we see at play in the passage I quoted, and how this is illustrative of the dynamic we saw at play in Plotinus and Heraclitus.

In going forward to Circe’s palace, the men become conscious of the singing. A beautiful and enchanting voice, igniting in them the desire to know more of where it came from. Their ears caressed, and their imaginations stirred, the urge to enter the palace is ignited in the hearts of the men. This urge, and the desire to act on it, is symbolized by Polites, the man who decides that they should call out to the woman singing. I want to show you that in this tale, we can see Polites as symbolizing the irrational part of our soul and what it entails to follow this part. Whereas Eurylochus, the one who doesn’t enter Circe’s palace, symbolizes the rational part of our soul and what it entails to follow this part. For in this moment, confronted with the sense pleasure offered by Circe’s voice, and the urge to enter ignited by this pleasure, the men have a choice. They know all too well that something is off, and that this is all too good to be true. This was already evident when they were surrounded by the tame wolves and lions. It is said:

“so they came nuzzling round my men—lions, wolves with big powerful claws—and the men cringed in fear at the sight of those strange, ferocious beasts… but still they paused at her doors, the nymph with lovely braids.”

(Homer, Odyssey, X 240).

They know that something is off here, their natural urge is to keep away from such dangerous beasts, and they know it is odd that the beasts are so peaceful. Yet still, they go forward because they hear the enchanting voice of Circe. At this moment, they have already decided that they should follow the pleasure offered by their senses, and not common reason, which tells them to stay away from dangerous and treacherous situations. And so they look a little deeper into the pleasure, they listen a little harder, and they go closer to the palace.

Most interesting is the passage that follows, and the differing attitudes of both Polites and Eurylochus. If we take Polites to stand for following the irrational part of our soul, and Eurylochus to stand for following the rational part of our soul, we see clearly how this dynamic of renouncing reason works. Both men are confronted with the same sense pleasures —the same singing. But focussing on it, Polites decides to follow this pleasure and the urge to enter the palace that it ignites in him. Important here is that Polites consciously decides to follow this urge. It is he himself that first enables Circe to turn him into a pig. It is he himself that decides to call out to Circe. Remember the dynamic we saw in Plotinus. Before we are addicted to something, before we are enslaved by matter, it is we ourselves that enact this primal act of renouncing reason and following pleasure. It is only because of this first choice that all of the men have, that Circe will later be able to turn them into pigs.

The lesson here is that we are never just deceived, but that we allow ourselves to be deceived. And what decides on the outcome is this very first moment, when both reason and pleasure are still heard clearly, but we choose pleasure over reason. For having chosen pleasure, it is often too late, or at least it becomes harder, to listen to reason. For we have now already decided to let our urges sound louder than our rational calling. The importance of the present moment, this is expressed here. As Epictetus writes:

“Remember that now is the contest, and here before you are the Olympic games, and that it is impossible to delay any longer, and that it depends on a single day and a single action, whether progress is lost or saved.”

(Epictetus, Enchiridion, 51.)

We must be vigilant at all times, this is what the Greeks are telling us.

The Odyssey teaches us that we are never just deceived, but that we allow ourselves to be deceived. This is illustrated perfectly by Hieronymus Bosch’s The Conjurer. In this painting, we see a man’s purse being stolen because he is too focused on the magic tricks being enacted by the conjurer in the painting.

All the other people watching are not being deceived. They observe the same magic tricks, but they stay firm in their frame and are still conscious of their surroundings. But the person being deceived is different, he completely puts his attention with the game, he bends his back, loses his posture, and thus loses consciousness of himself. And consequently, his purse gets stolen by the man behind him. Deception is part of the human experience. We are deceived continuously by different people, thoughts, opinions, pleasures, urges. But the choice is still ours to go with these things, or to remain firm in ourselves, and refrain from listening. Everyone faces deception, but not everyone lets himself be deceived. We all watch the conjurer’s game, but we have a choice to let ourselves be deceived by it or not.

Polites is much like the deceived person in Bosch’s painting, he puts all of his attention on the voice of Circe and follows his urge. Once inside, he is given a potion, and he is turned into a pig. Once a pig, he loses all consciousness of his own rational task —to return home to Ithaka—, he becomes incapable of choosing anything but sense pleasure, and he spends his days gorging himself like a pig. No longer a man, following reason and his own rational desires, but being completely determined by his senses, a mere slave to his surroundings.

Eurylochus expresses a different attitude. He is exposed to the same sense-pleasures, he hears the same voice. But in this crucial moment, where both reason and senses are still heard, he decides to follow reason, and to step back, before it is too late. He expresses the importance of the present moment, this constant vigilance, this knowledge that “now is the contest, and here before you are the Olympic games, and that it is impossible to delay any longer, and that it depends on a single day and a single action, whether progress is lost or saved.” Before we become slaves to our surroundings, and to the mere gratification of immediate desires, we have this primal choice —to listen to reason, or to listen to our senses. And it is this choice that determines whether we will reach Ithaka, our home where we are supposed to be, or whether we will drift further away from our natural place by living as pigs.

The Odyssey expresses this basic dynamic of the soul that we saw in Plotinus —to follow reason and thus stay true to ourselves as rational animals, or to follow what the senses deceive us into doing, and become as pigs. To remain ourselves, and thus strengthen our connection to the Divine One, or to flee from ourselves and strengthen our connection to matter.

Sources:

Plotinus. The Enneads. Edited by Lloyd P. Gerson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. London: Penguin, 1996.

Charles H. Kahn. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Epictetus, Enchiridion. Translated by W. A. Oldfather.

Plato, Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper. Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997.