This is a text on the idea of ‘philosophy as a way of life’, made popular by the French philosopher Pierre Hadot. In antiquity, philosophy was not just theory. Rather, it was an all-encompassing training of the individual, so as to transform him into a free man. What can this mean for us? Do we still dare to practice philosophy, as a way of life?

Going into the future, I will write more on this topic, and paid subscribers will receive extra texts focusing primarily, but not exclusively, on ‘philosophy as a way of life’. Read through to the end for more information.

I. What is philosophy?

It is often lamented, that philosophy is not what it used to be. Philosophy has become a dry theoretical exercise, and is no longer a way of life. It is the mere gathering of information, and no longer a formation. Some even dare say, that it has become indoctrination. We witness this transformation, for better or for worse, from philosophy as a way of life, to philosophy as a purely theoretical discipline. When Socrates proclaims that “those who practice philosophy in the right way are training for dying”(Plato, Phaedo, 67e), it is clear that philosophy is not the designation for a mere theoretical activity —a body of knowledge, and a method for gathering knowledge. Rather, this “training for dying” that is philosophy entails the formation of the entire individual. The discourses that we call philosophy have as their end not the gathering of knowledge, but the transformation of the individual. No mere learning, but a violent ‘paideía’; a discipline of mind and body, a training of the philosopher, askèsis.

Nietzsche knew of the importance of such formation when he dreamt of ‘breeding’ the ideal thinker. And why would one not dream as Nietzsche did? For it is undeniable that there is an intimate connection between one’s way of life, and one’s manner of thinking. The two are inextricably linked. And as such, we cannot leave ourselves to just think, without taking into account our way of life. There has to be a discipline of the philosopher, before we can speak of philosophy as a theoretical discipline. And the idea that ran through the Ancient conception of philosophy as a way of life, and which Nietzsche too divined, was that the truth could only be seen by those who mould their lives in accordance with it. The truth is there, but it is only visible for those open to it. Perhaps it takes the willing exposure to hardship of the Stoics, perhaps it takes the mountain air that Nietzsche sought.

Common to all philosophy is the idea that theory and life are not separate domains, and that philosophy happens in their union. Philosophy might have become a mere theoretical exercise, and is no longer a way of life seeking to transform the individual. But to make it a way of life anyways, remains a necessity. For we all know that a clear mind is needed to view the truth, and that a capable body is needed to be able to handle the truth.

II. A new life

Heraclitus says that:

“Eyes and ears are poor witnesses for men if they have barbarian souls.”

(Heraclitus, XVI. (D. 107, M.13))

Our soul must be in order, for us to be able to see the order of the universe. This is the Ancient idea that caused philosophy to emerge.

A blind person can’t see light, and someone in love with a lie he tells about himself, can’t see himself for what he really is. Someone addicted to alcohol, will not admit the truth of his destructive behaviour to himself. And the coffee addict has all the studies to back up his addiction. The truth is twisted, by those who don’t live in a manner that allows them to receive the truth.

“To the foolish the truth is bitter and unpleasant, while falsehood is sweet and agreeable; and likewise, I believe, for those who have diseased eyes, light causes pain, while darkness brings freedom from pain and is welcome, because it prevents them from being able to see.”

(Diogenes the Cynic, Sayings and Anecdotes, §289)

This is the idea that allowed philosophy to emerge as a way of life. And in many ways, we are miles removed from this idea. We all affirm, that the observer influences the observed, but who accepts the consequences? Who accepts, that we should not only study the observed, but also train the observer?

We often presume that you are a philosopher when you know the books which we categorize as philosophical. When you have read this literature, which everyone can do provided they have enough time, then you are a philosopher. It is the possession of the theory, that determines whether you are a philosopher. This is entirely different from how a philosopher was viewed in Antiquity. For often, the most praised philosophers had read very little. We think of Socrates, we think of Diogenes, and we think of all those forgotten philosophers who spent their lives in devotion to wisdom. If the philosopher was not known by his knowledge, than by what was he known? It was by his way of life, by whether or not he lived a philosophical life. Whether he strained himself to attain the ideal of the philosopher. Ancient thought was driven by this pursuit; to become a philosopher, and only then, could one speak of ‘philosophy’.

What is this ‘way of life’? What is a philosopher? It is a way of life in accordance with truth, and the philosopher is he who achieves this end. It is a way of life in which there is no gap between what one says, and what one does. A way of life in which one lives in such a manner so that one might find the truth, and in which one has the courage and strength to live in accordance with it.

Philosophy is defined as the love of wisdom, ‘philo’-‘sophia’. And so, we must become a person who loves wisdom, who is open to it in the most radical manner possible, and only then can we achieve wisdom. Wisdom being nothing but the attainment of this ideal; a person living in accordance with truth. For if this has been achieved, the truth will shine on us naturally. Like the person with eyes intact will naturally see light. Becoming a philosopher, this is what philosophy meant.

What is a philosopher? The sage, the fully autarchic human being, free, dependent on nothing, living according to reason every step of his life, living in truth. In this world, everything abides by the law of cause and effect. And as such, we are determined through and through by our environment. Nature and culture have us programmed. But man is a peculiar animal, in that he has the possibility to deny his programming, to rise above this chain of cause and effect, and to take full control of his life. We can be programmed, but we can also program. We can follow reason, or we can follow the inclinations, opinions, and desires of ourselves and others. We can renounce being influenced by our environment, and become masters of ourselves. It is the pursuit of this, the hardest task one could ever undertake, that is the pursuit of the philosopher. A bold pursuit, to become more human than human, a fully reasonable animal. A reckless pursuit, barely human in intent. What is sought is not new knowledge, but a new life. The life of a God, a force influenced by nothing but itself, necessity incarnate, freedom.

III. The Ideal of philosophy

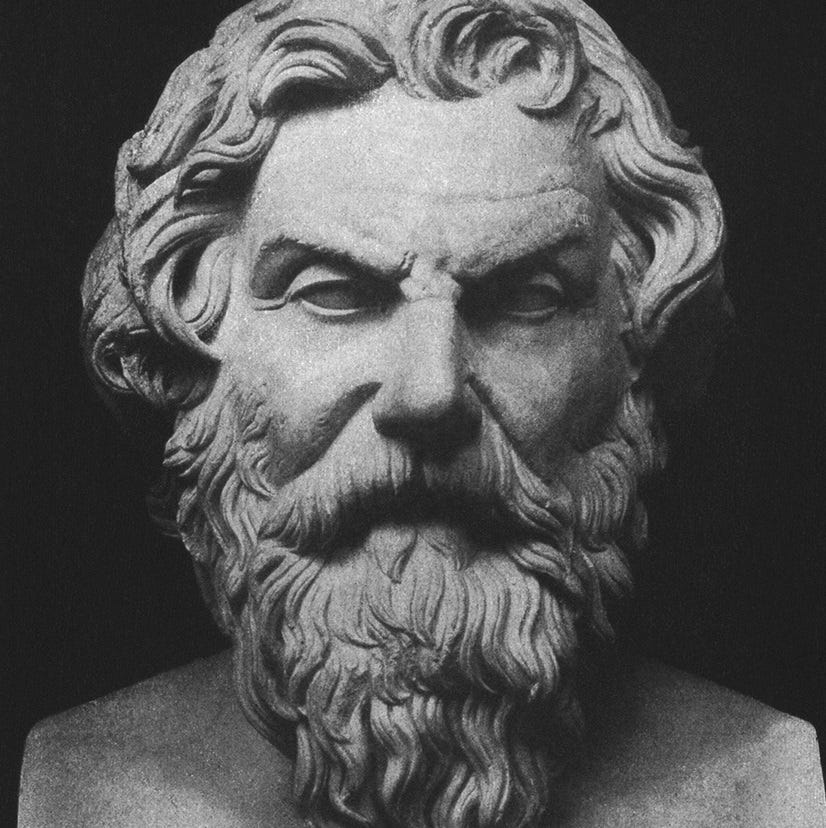

This ideal lives on still in Kant or Schopenhauer, it is fully visible in Descartes and Spinoza, and finds fierce expression with Nietzsche. To become a free human being, that is, to become more than human. Bound not to the fleeting concerns of the day, but to Reason. Bound not to the opinions of the masses, but to Ethics. Focused not on matter, but on our Soul. This ideal was embodied by Socrates, the man who sought to live his life according to reason, and by reason alone. Such a man does not follow his unnatural inclinations, nor does he follow the opinions of his environment, as is evidenced by Socrates’ death. The man against time, living outside of his time, to create a time to come. Socrates was often seen as the ideal, but many tried to live in a similar way, often driving the pursuit of autarchy to extremes. We think of Diogenes the Cynic. Nicknamed ‘the dog’, Diogenes roamed the streets of Athens with no possessions, surviving only off of the bare necessities, living the free life of the philosopher as radically as possible. His name meaning nothing but “Son of God who acts as a dog.” A man born from God, but only a dog in the eyes of the masses. Brought up by Reason and Nature, not by the opinions of society. He was not like those thinkers who nudge others into compliance through their discourses. Rather, Diogenes shamed others into virtue through displaying his way of life.

Living in this manner, Diogenes shows that it is possible to live as a free man, entirely in control of one’s way of life, living in virtue, even if one’s environment pushes one in the opposite direction. Living like this, without compromise, made Diogenes into a philosopher. All the anecdotes we have of him, —that he masturbated in public, lived in a barrel, or urinated on others—, are entirely unimportant compared to this mere fact; Diogenes showed that it is possible to live as a self-sufficient being, as a God, among humans.

The philosopher was often a private individual, someone who lived in a manner which was opposed to the opinions of his surroundings. He who lived in a manner opposed to the common way of living in the polis. And this is how the philosopher is condemned to live. For historically, it so turns out that living in accordance to truth, will make one live differently from the masses. Not that the philosopher must by essence be a solitary individual. Far from it, friendship and community are the greatest goods, but it happens to be the case that he always is. For the Greeks knew, that most only prefer to stuff themselves like cattle. Most are not interested in the attainment of freedom, most are not interested in philosophy. Philosophy, either the affair of the aristocratic, rising above the masses through virtue and courage, or the affair of the solitary, only at home with themselves.

“The best choose one thing in exchange for all, everflowing fame among mortals; but most men have sated themselves like cattle.”

(Heraclitus, XCVII (D.29, M.95))

IV. Deception & Health

Philosophy is interested in truth, and being interested in truth, it must also be interested in what prevents us from attaining truth. Lies, deception, falsity, illusion, —the horrors that prevent us from reaching our goal. If the attainment of truth is philosophy’s positive motivation, then the avoidance of what prevents us from attaining truth acts as its negative motivation. The love of truth, and the violent attack on all the lies, deceptions, falsities, and illusions that cloud our view. This love and this attack are inextricably linked, and in practice often amount to the same thing. For in dispelling an illusion through critique, the truth often becomes visible by itself. This is how Heidegger described phenomenology, as the method of letting the truth be shown by itself and from itself. We need only get out of Truth’s way.

But this double effort —love and critique—, can never be achieved in full, if philosophy is only taken to be a theoretical discipline, and not a discipline of the entire individual, as a way of life. Very concretely, the fat person is more likely to be deceived into getting three useless vaccines. And he who believes he needs to stuff his face 24/7 is more likely to suffer from the ‘locking-down’ of supermarkets. The coffee addict won’t be able to hold open his eyes to see the truth, when the supply-chain breaks down. He who is healthy in body and mind, doesn’t need anything outside of himself to feel safe, no useless supplements, and no vaccines. And he who doesn’t need a constant supply of junk-food, and can just as well not eat for a few days, might even perceive the removal of these warehouses of death as a good. He who doesn’t need his coffee to stay awake, will perceive clearly at all times.

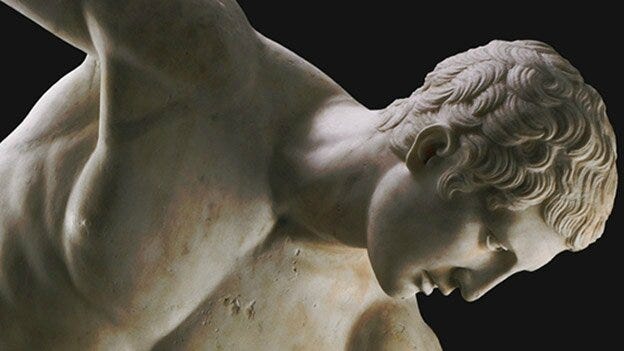

It is in this very concrete manner, that our way of life influences our thoughts. And it is this very simple observation, that stands at the core of the Ancient idea of philosophy as a way of life. From Plato through the Stoics and into Neoplatonism, there is always a delicate attention paid to the disciplining of the body. Not out of vanity, but because one knows that the mind influences the body, and that the body influences the mind. A double discipline, of both body and mind, this is what philosophy necessarily entails. For just as a sick mind will prevent us from grasping the truth, a sick body will keep us from allowing the truth to enter us. The importance of physical exercise affirmed by Plato, the various exercises to harden our discipline described by the Stoics, the affirmation of theurgy in Neoplatonism, and the contemplation of the Pythagoreans. To purify our body and mind from lies, so that the truth might enter. Next to the three classical branches of philosophy —logic, (meta)physics, and ethics—, we can add: discipline, physical exercise, and contemplation.

The question of truth leads us to the question of health, of strength. By necessity. We all know that a healthy mind requires a healthy body, and vice-versa. And if the highest activity of thought —philosophy—, is taken seriously at all, it must concern itself with health. But what is health? Is disease not part of life? You ask. What is strength? Is not our fragility our greatest strength? You ask.

Valuable questions, but perhaps questions which can only emerge once decay has already set in. Valuable questions, or only symptoms of an organism in distress?

Heidegger affirms ceaselessly that the human is the opening towards the truth. And it is the manner in which this human-being is formed that determines the degree to which the truth can enter. The truth is visceral, and so is the lie. For the truth must be lived, and undergone, often paining our egos along the way. But the lie must also be lived, when it means suffering from a bad habit, or dying from vaccine damage. When the lies of the ‘philosophers’ deceive you into forsaking your body so as to grow your mind, you will live this lie when you break your back from falling in old age.

V. Autarchy

We claimed that the philosopher attempts to become independent from bodily influence, a cause unto himself. But we must not deceive ourselves, down here in matter, we are both a body and a mind, inextricably linked through the greatest mystery. The Stoic Musonius Rufus explains:

“Since a human being happens to be neither soul alone nor body alone, but a composite of these two things, someone in training must pay attention to both. He should, rightly, pay more attention to the better part, namely the soul, but he should also take care of the other part, or part of him will become defective. The philosopher’s body also must be well prepared for work because often virtues use it as a necessary tool for the activities of life. One type of training would be appropriate only for the soul, and another would be appropriate for both soul and body. We will train both soul and body when we accustom ourselves to cold, heat, thirst, hunger, scarcity of food, hardness of bed, abstaining from pleasures, and enduring pains.” (Musonius Rufus, Lectures and Sayings §6)

There is both the training of the mind, and the training of the body. And both belong to philosophy. In a fragment describing the teachings of Diogenes the Cynic, we read:

“He used to say that there are two kinds of training, one mental and the other bodily. Through constant physical exercise, mental impressions are produced which facilitate the realization of virtuous actions. The one kind of training cannot achieve its full effect without the other, since good health and strength belong no less among the qualities that are essentially required, both for the soul and for the body.”

(Diogenes the Cynic, Sayings and Anecdotes, §105.)

The truth only occurs to those who have opened themselves to the truth. And it is this observation that conditions much of the form of Ancient literature. Many texts are written in the form of philosophical ‘protreptica’, manuscripts meant to inspire the reader to choose a philosophical life, and schooling the reader in the methods needed to attain such a life.

And once such a choice had been made to pursue a philosophical life, the next step was to train.

Dialectics, strength training, self-discipline, endurance, theurgy, contemplation. It is not merely by reading something that we will adopt it.

“Could someone acquire instant self-control by merely knowing that he must not be conquered by pleasures but without training to resist them?”

(Musonius Rufus, §6)

Evidently not. And hence these texts were meant to be read over and over, not to absorb more information, but to let the information find its influence in our actions. One was not encouraged to read like we read nowadays, scouring through article after article, absorbing more and more information. One was encouraged to read one text over and over, and only when one had moulded one’s life in accordance with the contents of this text, only then could one say that one understood it. The most famous example of such literature is Epictetus’ Enchiridion, a manual for the Stoic life, to be held close to oneself and read over and over. This was not only so that the wise philosopher could educate his pupils, no, this was the practice of the philosopher himself. It is said that Marcus Aurelius wrote his Meditations for himself. It was through writing, that the philosopher entrained the right thoughts and behaviours into his being. This is why philosophy is read or written; not to absorb knowledge, but to transform oneself.

VI. Philosophy today

Much has changed, and in many senses the climate that philosophy calls home —the University—, makes it impossible for philosophy to be a way of life. One cannot spend time training oneself towards freedom, a task which would take a lifetime. One needs to go through the curriculum as fast as possible, read all the unnecessary shit, and go from student to employee as soon as possible. One cannot live according to what one reads. Say one is specialized in Nietzsche or Aristotle, one studies these thinkers fiercely, and truly believes what they have to say. Now suppose one where to voice these opinions after having made them one’s own, wouldn’t one be in complete opposition to the newest ‘diversity and inclusion’-program of one’s employer? The university would be a battle ground in which no work gets done. In the current climate, philosophy as a way of life seems like an impossibility.

But as much as it is an impossibility, it remains a necessity. For if we live like pigs, we will be feared into a next scam pandemic. And if we do not expect the best from ourselves, we will not expect the best from our communities in all our political theorizing. If we are ashamed of ourselves, the self will be granted little role in our ‘philosophies.’ If we value matter over truth, materialism will ravage the world. In many senses, the truth is not to be sought, for the truth is merely what is. What should be sought is a way of life that allows us to see the truth.

And just like the sage, one must strive to live in truth in an environment that knows only lies and deception. Nothing has changed in this respect, truly nothing at all. And lamenting amounts to nothing, for it once more affirms the un-philosophical attitude of dependence. As Epictetus affirms:

“This is the position and character of a layman: He never looks for either help or harm from himself, but only from externals. This is the position and character of the philosopher: he looks for all his help or harm from himself.”

(Epictetus, Enchiridion, §48).

For before the philosopher is opposed to the opinions of society, the philosopher is at war with his own opinions. With his own weakness of mind and body, with the opinions floating around in his mind, that urge him to depart from reason. That trick him in doing what he knows to be wrong, that deceive him into a life of compliance, choosing pleasure over purpose. The outward fight against the world, is only the result of the inner fight the philosopher wages against himself. An arduous task of self-overcoming. And hence, training.

Whatever the state of the world might be, philosophy as a way of life remains a necessity, for our life influences our thoughts, and our thoughts influence our life. Our life determines our openness to truth. And so, philosophy as a way of life remains a necessity, at least if we value the truth. This Ancient discipline of both mind and body which we call philosophy, this remains the task. Even if we know full well that the attainment of the philosophical life remains an Ideal in the Kantian sense. A noble goal buried in our innermost essence, something which we strive to attain, but which we might never reach.

VII. Living in Truth

It is this —the necessity of philosophy as a way of life— that will colour much of my writing going into the future. And paid subscribers to Tólma will receive extra texts focussed primarily, but not exclusively, on this topic. Close readings, texts attempting to extract practical advice from important texts both Ancient and modern, sharing texts I discover, little (or longer) courses on specific philosophers and themes. This does not mean that I will only read the most evident authors in this tradition of ‘philosophy as a way of life’, such as the Stoics, Cynics, or Platonists. Philosophy is meant to transform the person, both through the thoughts that it offers, and the discipline of body and mind that it offers. And in this sense, all theoretical philosophy influences us. It is my conviction that the most abstract of metaphysical treatises can be transformational. In delving into the metaphysics of a certain philosopher, we are offered a new way of looking at the world, a new perspective. And as our way of looking determines what we will see, the philosophies we read bring us closer to the truth, or further away from it.… This does not mean distorting a deep work into just another list of useless self-help advice. Rather, it means allowing ourselves to read a text as it was meant to be read.

Spinoza’s Ethics can be seen as an abstract work of ‘theory’, but through learning his metaphysics, the book is meant to bring about an ethical conversion towards freedom. Through grasping the metaphysics, we transform our life. In this way we will look at the history of philosophy. For when philosophy is most alive, it is never mere theory, but always engaged in transforming our lives in their entirety.

‘A philosophy’ is like a pair of glasses, which offers us a new way of looking. But in fact it is much more, for it alters our eye itself. Thought influences biology, and biology influences thought. This is what I believe. And if we are interested in the truth, then this interplay between thought and life must be at the forefront of our interests. This is no new interest of mine, and if you have been reading this site you know this. Consider joining me. We often shy away from high ideals, but we should not kid ourselves. If you are interested in philosophy, if you are interested in the truth, than you should have an interest in striving to live like a philosopher, in living in truth. And this is not only so if you believe philosophy to be your vocation, for if philosophy is nothing but the pursuit of freedom and truth, of becoming the best human you can be, then why wouldn’t you be interested? To someone who said “”I’m ill-suited to philosophy’”, Diogenes the Cynic rightfully replied: “‘Then why live at all, if you have no interest in living well?’”(Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §109)

Whatever your vocation might be, or wherever your interests might lie, you are alive, and you think. And as philosophy is the pursuit of living and thinking well, and having your life and thought be in accordance with each other, philosophy is for you. That is, if you seek not merely to live, but to live well, philosophy is for you. If you seek not merely to coast through life, self-same at all times, but seek to transform your life for the better, philosophy is for you.

You might not have a major interest in the philosophical books of old. You might be an athlete, why would you bother engaging your mind? You might be an entrepeneur, why would you waste your time reading philosophy? You might work in manual labour, why would you also labour through texts? But you do not realize, that whatever your activity might be, philosophy is for you. By subscribing, you will make this task of philosophy a lot less daunting. I will scour the history of philosophy for those pieces of information and advice that are truly transformational, and offer you the lessons learned. Applying them is up to you, but I will help you get on the path. We go beyond the familiar summaries of what people call ‘stoicism’ nowadays, deformed pieces of self-help, only meant to sell to the masses. You must know that true value is often to be found in the more obscure texts, in those philosophers people have never heard of, pushed away by the status quo and political correctness of our times. Or in those great thinkers of which we all know the name, and of which we all feign knowledge, but no one actually every reads. You will discover that there is often a much more vital core to philosophers which we deem unimportant nowadays. There is much more to philosophy than the familiar names. And throughout this history, obscured by dry theory, there is a vast treasury of teachings to transform both your mind, body, and soul. Through looking at these texts of old, we ask ourselves, what can philosophy as a way of life mean today? What can it mean for ourselves?

The Pre-Socratic philosophers, Pythagoreans, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, the Cynics, the Stoics, (Neo)-Pythagoreans, (Neo)-Platonists. These are key sources for our vision of philosophy as a way of life. But also the Medieval philosophers, the Cartesian program for transforming mind and body by way of scientific method, Nietzsche’s program for constructing the Übermensch, the contemplative phenomenologists of the 20th century such as Michel Henry or Louis Lavelle, and many more. All traditions of philosophy are open to us to learn from, provided they are alive. We will look primarily at the Western tradition, but the entire world is open to us.

First up we will take a close look at Diogenes the Cynic. There is hardly a philosopher who expresses more the ideal of ‘philosophy as a way of life.’ For with Diogenes, philosophy is only a way of life, a way of disciplining mind and body, and theory is entirely unimportant. As way of life, philosophy engages with theory, in order to achieve the ideal of the free man, the sage. And Diogenes believes that if this is the case, we might as well just skip theory, and start living like a free man right here and now. All this theorizing that most philosophers do, Diogenes sees it as distraction. They want to think to become a better human, but only to postpone actually bettering themselves! This is Diogenes’ viewpoint. Whether you agree with this or not, there is still much to learn from Diogenes. For isn’t it the case that we often know very well what to do, but our problem consists in not doing it? Don’t we know perfectly well how to be free from influence and slavery, but are too afraid of doing it? We know that a healthy mind rests in a healthy body, and that a healthy mind creates a healthy body, and we know how to achieve health, but we are just not capable of doing it. We think one thing, and we do something else. This is the weakness that Diogenes fought throughout his life, throughout his philosophy.

Can we not learn much from Diogenes? For we too live in a time of confusion. So many opinions floating around, but no real thought. So many distractions, so many different ideas and principles to choose from, distracting us from the task at hand; to simply live in truth. Diogenes sought to overturn all the values of his city, the opinions held by what he called the less-than-human masses, the corruption of those who philosophize in their ivory towers, focused only on books, but never on life. And through his life itself, Diogenes sought to show that there is a different way, a different truth, not determined by social currency or common opinion, but by the simple speech of a man living in accordance with nature.

Sources:

Charles H. Kahn. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Epictetus, Enchiridion. Translated by W. A. Oldfather.

Plato, Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper. Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997.

Diogenes the Cynic, Sayings and Anecdotes. Translated by Robin Hard. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Musonius Rufus, Lectures and Sayings. Translated by Cynthia King. 2011.

Truth as lived, truth as a way of life— that is missing in today's understanding of truth as information, as correspondence to the facts, as data and the transmission of data. Some truths are silent, demanding a response from the whole person, requiring action and not conceptual representation. And perhaps this means equating the true and the good: ideas that are held apart in this schizophrenic age, stuck between scientific objectivism and social justice moralism.

The law of non-contradiction seems especially important to truth and goodness: "a way of life in which there is no gap between what one says, and what one does." This seems to be the beginning of wisdom, as it means not believing that which cannot be lived.

Thanks for the read, Tolma. The references are a help, too.