“Eén gek kan meer vragen dan zeven wijzen beantwoorden kunnen.”

“One fool can ask more questions than seven wise men can answer.”

It is often said, that philosophy consists in questioning. Philosophy begins in wonder, it is said. And what is wonder, but the experience of something that was at first merely evident, becoming question-worthy? Philosophy seeks to question seemingly evident opinions in order to arrive at truth, and hence, philosophy consists first and foremost in questioning. This fact of philosophy leads Michel Meyer to proclaim that:

“What imposes itself as first in the interrogation for what is first, is the questioning of what is first itself. This is why questioning is the principle of thought itself, the philosophical principle par excellence.”

(Michel Meyer, De la problématologie, 11)

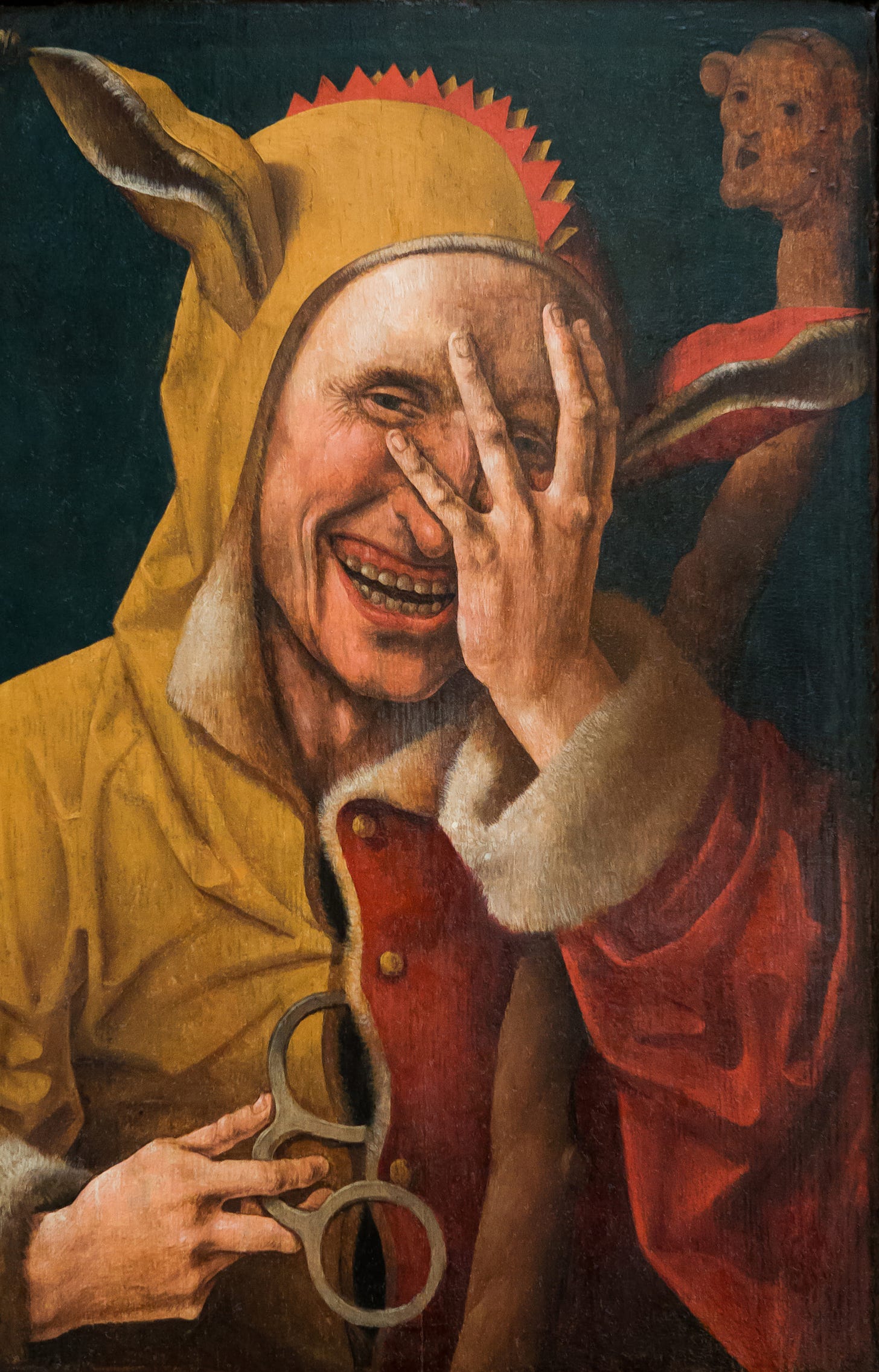

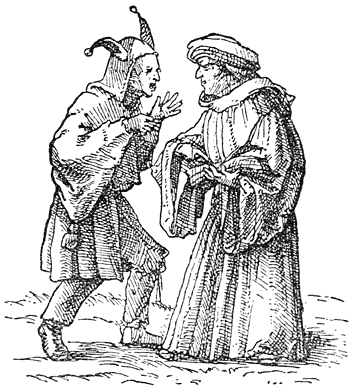

Philosophy consists in questioning, evidently. Questioning is evidently a part of philosophy, but does it explain the essence of philosophy entirely? For if we ask, who is it that questions? It is evidently not only the philosopher that questions. Everyone questions, also non-philosophers. And if we were to find someone who questions more incessantly and more intensely than the philosopher, wouldn’t he be found to be the true philosopher? And who among us, questions the most? The child questions, the fool questions, the madman questions. For the child, the world is entirely new, a place of wonder, in which everything is question-worthy, and hence, the child has no end of questions to pose its parents. The archetypal fool of the middle ages, the jester, was he whose business consisted in questioning the thoughts and customs of higher standing individuals. And for the paranoid schizophrenic, the most innocent of phenomena, are worthy of paranoid investigation. The child, the fool, and the madman, three archetypes for philosophy? We would lead ourselves to believe so, if philosophy amounts only to questioning.

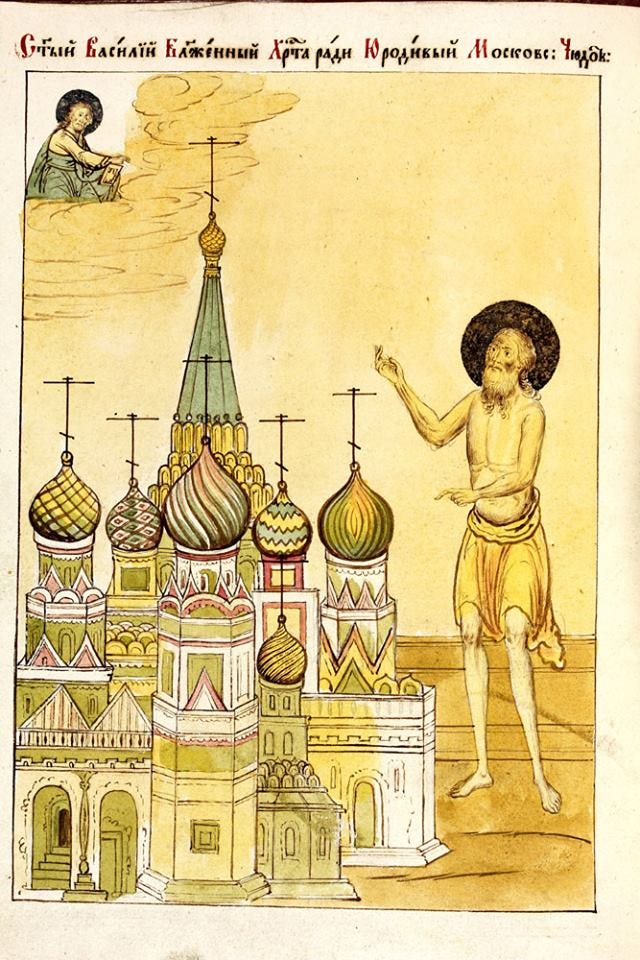

This simple observation, that perhaps the child or the fool are more expressive of the essence of philosophy than the philosophers themselves, knows a long history. A large part of Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly (1511), is devoted to showing that the virtues that we attribute to philosophers, are in fact more present in folly. The philosopher is he who speaks the truth, but he is prevented from doing so, because he doesn’t want to harm his reputation. The fool however, doesn’t care in the slightest about what people might think, and he speaks his truth without fear. The philosopher is he who questions authoritative opinions, but isn’t the fool much more radical in this regard? It was the medieval jester who questioned and mocked the king most intensely, the philosophers only obeyed. This simple observation has a long history, and finds expression in many different philosophical and religious strains of thought. There is the idea of ‘foolishness for Christ’, which finds one of its most intense expressions in the yurodivy of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. These ‘holy saints’ took seriously the saying that “the wisdom of this world is foolishness in God’s sight.”(1 Corinthians 3:19) Hence, they tried to attain the highest degree of foolishness in this world, so they could attain the wisdom that resides in God. Much like the jester, these saints made it their business to mock the beliefs and habits of both common people and aristocracy. They did so, not only in thought and speech, but also in their acts. They were known to go around naked and they urinated on churches, thus shocking everything and everyone. All in an attempt to show the insignificance and foolishness of this world, and remind people of the significance and wisdom of God. Much like the behaviour of the ancient Cynics. Concerning these yurodivy, Dostoevsky said:

“We can suspect that beyond the mask of such stupidity something hides itself, who knows what! A different reason, not a human reason, but a reason that is not of this world.”

(Dostoevsky, cited in Cezary Wodzinski. Saint Idiot, 25-26)

In the much different climate of 20th century ‘post-structuralist’ philosophy, this time ignorant of God, the archetype of the fool arises anew. Foucault wrote his Madness and Civilization, which tried to grasp the significance of madness for deconstructing the ‘regime of representation.’ The experience of madness is able to look past the borders set by our limited human reason, and can thus offer a fuller picture of reality. Much the same, Gilles Deleuze saw in madness an extreme of what it would mean to break with the ‘dogmatic image of thought.’ Every philosophy or system of thought, Deleuze said, is rooted in certain pre-philosophical presuppositions. Whenever we do philosophy, we do so based on certain pre-suppositions that aren’t visible in the philosophy as such, but are nonetheless pre-supposed by this philosophy. These pre-suppositions are so sedimented into our manners of thinking, that they are barely the object of consciousness, and it takes exceptional self-reflection to be able to see them. But, the schizophrenic or the psychedelic enthusiast is able to go beyond the borders set by consciousness, and is thus able to analyze the presuppositions of conscious thought. Deleuze writes:

“Schizophrenia is not merely a human fact, but a possibility of thought, which reveals itself only in the abolition of the image [of thought].”

(Deleuze, Différence et Répétition, 192.)

That is, madness is not something that happens to us as an accident, and thus constitutes a falsification of sane thought. Rather, Deleuze claims, schizophrenia gives us access to the true depths of thought. As what we call ‘sane thought’, is already a first falsification or blockage put on this essence of thought which resides in a pure chaos of “schizophrenic depth”, a chaos more easily accessible to the schizophrenic.(Deleuze, Logic of Sense, 161) Of course, Deleuze was not encouraging philosophers to go mad or to take insane amounts of drugs. Although many young students were already too fascinated to truly listen, and had to pay the consequences. Or had they listened too closely? Deleuze did claim, that there was much to learn from going just a little bit mad. His philosophical heroes in this regard are figures like Artaud, Nietzsche, Fitzgerald, or Lowry. These thinkers, all afflicted by some type of madness or drug-use, claimed that the states reached in madness or drug-use allowed them to go beyond the rigid structures of thought, and reach for its true essence, so that they might bring back wisdom to their writing. It is worth quoting a passage from Deleuze in full:

“When Fitzgerald and Lowry speak of this incorporeal metaphyiscal crack and find in it the locus as well as the obstacle of their thought, its source as well as its drying up, sense and nonsense, they speak with all the gallons of alcohol they have drunk which have actualized the crack in the body. When Artaud speaks of the erosion of thought as something both essential and accidental, a radical impotence and nevertheless a great power, it is already from the bottom of schizophrenia. Each one risked something and went as far as possible in taking this risk; each one drew from it an irrepressible right. What is left for the abstract thinker once he has given advice of wisdom and distinction? Well then, are we to speak always about Bousquet’s wound, about Fitzgerald’s and Lowry’s alcoholism, Nietzsche’s and Artaud’s madness while remaining on the shore? Are we to become the professionals who give talks on these topics? Are we to wish only that those who have been struck down do not abuse themselves too much? Are we to take up collections and create special journal issues? Or should we go a short way further to see for ourselves, be a little alcoholic, a little crazy, a little suicidal, a little of a guerilla—just enough to extend the crack, but not enough to deepen it irremedially?”

(Deleuze, Logic of Sense, 162)

So what are we to do? Sit safely on the shore, or go a little crazy? I wholeheartedly agree that philosophy should be more than ‘abstract thought’, and that it should be ‘lived’. But I am pretty sure this shouldn’t mean becoming an alcoholic or going mad. Deleuze claimed he barely left his apartment, except for a short daily walk around the block. Perhaps he should have gotten some more sunlight, sought some more of Nietzsche’s ‘mountain air’, and Lowry’s alcoholism wouldn’t have been so attractive.

In any case, what is common to all these examples, is the suspicion that in childish wonder, in foolishness, or in madness, the true heights of thought or philosophy are to be attained. Why? Because in all these experiences, what is usually evident, becomes question-worthy. The most normal of natural phenomena, ignite infinite questions in the child. The most accepted of social customs, become an object of mockery for the fool. The most un-questioned presuppositions of thought, become an object of inquiry for the schizophrenic. And if philosophy consists in questioning, it follows that madness is where philosophy should be sought. But is this all there is to it? Either be a mediocre sane philosopher, or go through the cracks to become a real philosopher? In the Deleuze passage I quoted, there is an interesting distinction he makes. He says:

What is left for the abstract thinker once he has given advice of wisdom and distinction?

There is a distinction made between the abstract thinker, to which is attributed wisdom and distinction, and the ‘living’ thinker, to which is attributed peaking beyond the veil of madness to question distinctions. Here, with Deleuze and similar thinkers, philosophy should no longer seek wisdom or distinction, but should seek critique and confusion. Here, the philosopher no longer seeks health of spirit, but a certain madness. Life should not live in accordance with thought, but life should go beyond the boundaries set by thought, and thought should go beyond the boundaries set by life. “Life goes beyond the limits set by knowledge, and thought goes beyond the limits set by life.” (Deleuze, Nietzsche et la philosophie, 116)

Not madness for its own sake, but to pass through it, so that a greater sanity is reached on the other end. Sadly, most never pass through to the other end, but only end up rotting in the middle. I quote again from Deleuze’s Logic of Sense:

“If one asks why health does not suffice, why the crack is desirable, it is perhaps because only by means of the crack and at its edges that thought occurs, that anything that is good and great in humanity enters and exits through it, in people ready to destroy themselves—better death than the health which we are given.”

(Deleuze, Logic of Sense, 165.)

This is essential, wisdom and health of spirit are no longer sought. What is sought is a way of thinking that goes beyond wisdom, and a life that goes beyond health. Why? “better death than the health which we are given.” It is no surprise that the entirety of Deleuze’s philosophy consists of an attack on everything ‘given’. Nothing is ever given, but everything is constructed. The desire for truth is not given; man does not seek by nature to know, but has to be shocked into a search for truth. Personal subjective identity is not given, but has to be created from ‘pre-subjective’ material individuations. Everything that is given, is in fact something that was once created. The Ideas are not discovered, they are created by a thinker. And hence, for such a philosophy, the fool and the madman become the archetype of the philosopher, he who questions everything that is given; customs and truths. Philosophy is no longer the search for wisdom, but the activity of boundless questioning. Where philosophy used to consist in a balance between critique and wisdom, philosophy now consists only of critique.

But, what is wisdom? Deleuze sketches the pursuit for wisdom as a sort of submission to what is given. He who seeks wisdom, seeks to become one with Nature and Reason and seeks to live accordingly to the ends set by Nature and Reason, in both word and deed. Opposed to this, Deleuze sketches a different image of the philosopher, opposed to wisdom, and supposedly originating in Kant, who “opposes to wisdom the image of critique: we, legislators of Nature.” (Deleuze, La Philosophie Critique de Kant, 23) Of course, as much as in Kant we become ‘legislators of nature’, we legislate according to laws given by Reason. Deleuze himself, in the vein of Shestov and others, seeks to be done with the idea that anything whatsoever is given. Nature gives no laws, and neither does Reason. There is nothing to comply to, for nothing is given, and everything is created. In such a scheme, the idea of wisdom as living in accordance with eternal truths perishes. There is nothing to live in accordance with, as there is no eternal truth. Nothing is, everything becomes. And more, everyone who does claim to seek to live in accordance with eternal truth, is nothing but an imposter, who seeks to either deceive by presenting his specific values as eternal, or who seeks to flee this life out of resentment for this life. Deleuze speaks vehemently about Plato:

“Mania inspires and guides Plato. Dialectics is the flight of ideas, the Ideenflucht. As Plato says of the idea, “it flees or it perishes…” And even in the death of Socrates there is a trace of a depressive suicide.”

(Deleuze, Logic of Sense, 131)

A powerful thinker and historian of philosophy, but one cannot help but suspect a form of resentment in Deleuze himself, a profound dissatisfaction with how things are. In his later works, Deleuze speaks continuously about the ‘shame of being human.’ For him, the essential sentiment of human existence, is one of shame for one’s existence. A profound discontent, that urges one onwards towards a ‘greater health’, i.e. madness. Better to be a madman than to comply with how things are. Critique and deconstruct everything, in thought and in life, so that hopefully, something better than human is reached on the other end. This desire to have philosophy become a way of changing oneself, is as old as philosophy itself. But where it used to mean changing oneself so as to live and think in accordance with eternal laws, seeking a union with what is, it now means changing oneself so as to live and think as divergent as possible from any laws, seeking not union, but dissolution. Seeking not an identity with Nature, but the most radical difference from Nature. One sought to critique the false opinions and false laws of humans, in order to arrive at eternal truth and eternal law. Now one seeks to critique all forms of knowledge, and all forms of law. For, philosophy consists in questioning, doesn’t it? Regardless of what might be in front of us, everything deserves to be questioned into oblivion.

Our proverb: “one fool can ask more questions than seven wise men can answer”, is evidently used for those who think that questioning is what it means to think. And can be perfectly applied to a philosopher such as Deleuze. If philosophy consists in questioning, it follows, that one must believe that the fool is more of a philosopher than the wise man. One no longer seeks oneself by living in accordance with eternal truth, one now seeks to dissolve oneself in the madness of becoming. No truth to be found, only an endless question-mark.

Of course, an enormous transformation has occurred from the image of the fool as seen in the fools for Christ or the medieval court-jesters, to the madness of Deleuze. The former seek to act and think as a fool, but only in order to reach the wisdom of God. They seeks to question the opinions and laws of the worldly king, but only in order to show clearly the eternal truths and laws of the heavenly King. It is foolishness for the world, in order to reach the wisdom of God. The contemporary image of the fool, knows no such eternal truth. And hence, it is a questioning, ad infinitum. The world is not questioned, to uncover an underlying truth. The world is questioned, to uncover even more questions, without end.

We are confronted with two images of the philosopher: the fool who questions, and the wise man who knows. He who ceaselessly questions what is given, and he who seeks to abide in what is given. He who seeks to depart from what is, and he who seeks to become one with what is. He who seeks to question to uncover, and he who seeks to question to question. It is no wonder that Deleuze had a distaste for phenomenology; the method Heidegger described as the attempt to “to let that which shows itself be seen from itself in the very way in which it shows itself from itself.” (Heidegger, Being and Time, §7)

What constitutes the difference between these two modes of thinking, is whether one believes that there is such a thing as a ‘given’, or not. Is there something that is, prior to any questioning? Or is everything a possible subject of a questioning ‘deconstruction’? Michel Meyer said that philosophy consists in questioning, by essence. Why? Because philosophy starts by questioning. As it is said, philosophy starts in wonder, in the experience of something as being question-worthy. But does it? For before I experience wonder, I exist. My existence is true, before I am able to wonder about this existence. Is it not? I know the sun to be there, before I am able to question how it moves. But, it is said, this is the perspective of the common man. The philosopher however, is he who does question these things. The philosopher is he who bathes in wonder, more than the common man. The philosopher is he, who is able to look at the world like a child, full of wonder, everything new, everything question-worthy. But is he?

In Descartes’ Passions of the Soul, a distinction is made between ‘wonder’(l’admiration) and ‘astonishment’(l’étonnement). Wonder is defined as “a sudden surprise of the soul which brings it to consider with attention the objects that seem to it unusual and extraordinary.”(Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §70) In the experience of such wonder, the object of wonder impresses itself with much more force in the brain than other objects, and hence, the object of wonder is perceived as “something unusual and consequently worthy of special consideration.” Accompanying this, excessive bodily energy flows to that place in the brain where the object is impressed. And at the same time, energy flows into other parts of the brain and into the muscles so that the sense organs can make sense of what is impressed. There is thus both the wonder, which is an excitation in the brain that leads us to excessively focus on the object, but there is also an equal distribution of energy to the muscles in the body, so that we can make sense of the object in question. In other words, not all energy flows to the object in question, and as such, we can still understand the object in how it relates to everything else that impresses us. I see a type of animal that I have never seen before and this strikes me with wonder; a lot of energy goes to the place in my brain where this new sight is processed. But there is still energy going to other parts, and hence I am still aware of everything else surrounding the animal, trees, sensations, memory, etc. There is a healthy balance between the unfamiliar and what I already know.

Astonishment on the other hand, is defined as an excessive wonder in which all of the bodily energy goes to the object of wonder.

“This element of surprise causes the spirits in the cavities of the brain to make their way to the place where the impression of the object of wonder is located. It has so much power to do this that sometimes it drives all the spirits there, and makes them so wholly occupied with the preservation of this impression that none of them pass thence into the muscles or even depart from the tracks they originally followed in the brain. As a result the whole body remains as immobile as a statue, making it possible for only the side of the object originally presented to be perceived, and hence impossible for a more detailed knowledge of the object to be acquired. This is what we commonly call ‘being astonished.’ Astonishment is an excess of wonder, and it can never be other than bad.”

(Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §73)

Wonder is a great thing, and very necessary for philosophy. As it makes us investigate those things that appear unusual to us. What is ‘unusual’? Something of which we were previously ignorant. Wonder is thus the passion that drives us to seek out knowledge about things of which we were previously ignorant. Hence, for the child, having little experience, everything is still unusual, and thus everything is question worthy. In the as of yet un-moulded brain of the child, everything impresses itself intensely. The philosopher is he who is able to retain this childlike disposition of wonder in old age. He is not satisfied like most children, when their parents have answered all their questions, but he proceeds to question. Contrary to the goodness of wonder, astonishment “can never be other than bad.” Why?

“More often we wonder too much rather than too little, as when we are astonished in looking at things which merit little or no consideration. This may entirely prevent or pervert the use of reason. Therefore, although it is good to be born with some inclination to wonder, since it makes us disposed to acquire scientific knowledge, yet after acquiring such knowledge we must attempt to free ourselves from this inclination as much as possible.”

(Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §76)

Wonder is a good, because it drives us to escape our ignorance and acquire knowledge. But excessive wonder, is never satisfied with knowledge, and seeks to wonder even more, never ready to let itself be tamed. Until in the end, it questions the most insignificant things, having lost sight of what is truly worthy of wonder, and what not. In astonishment, wonder is no longer wonder for the sake of acquiring truth, but wonder turns into wonder for wonder’s sake. There are roughly three dangers in excessive wonder:

The questioning of insignificant things. If wonder were good in itself, and a characteristic of the good philosopher, then a person who seeks to investigate every person which hides behind a number in a phonebook, would be a philosopher. This is evidently not the case. The questioning ignited by wonder is only a sign of a healthy spirit, when one wonders about those things worth wondering about, and leaves alone those which aren’t.

The questioning of things which shouldn’t be questioned. For Descartes, there are things which are so evident in themselves, for example the existence of ourselves, that it is a sign of stupidity to question them into oblivion. One can become so gripped by the excitement accompanying wonder, that one seeks to question those things that are beyond questioning. We question so hard how something is possible, that we forget that it is.

Losing sight of the whole. In astonishment, all bodily energy goes towards the object of wonder, and one thus loses sight of the whole. As such, it becomes impossible to understand how the object of wonder is to be fit in to everything surrounding it. We can classify the dangers of excessive specialization in the sciences under this. A medical scientist becomes so obsessed with one organ of the human body, that he has no attention for everything else, thus losing sight of the fact that the workings of the body can only be understood as one whole.

In this, wonder can never be seen as an end in itself, but must only serve as a sign that puts us on the path to wisdom. Balance, between wonder and knowledge. We read Descartes again:

“Moreover, although it is only the dull and stupid who are not naturally disposed to wonder, this does not mean that those with the best minds are always the most inclined to it. In fact those most inclined to it are those who, although equipped with common sense, have no high opinion of their abilities.”

(Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §77.)

The best minds are those who are able to find a balance between wonder and knowledge. And they know what it is that merits wonder, and what is insignificant. The worst of minds however, are never content to make this distinction, and only seek out wonder for wonders sake:

“this is what prolongs the troubles of those afflicted with blind curiosity, i.e. those who seek out rarities simply in order to wonder at them and not in order to know them. For gradually they become so full of wonder that things of no importance are no less apt to arrest their attention than those whose investigation is more useful.”

(Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §78)

Everything is of interest, and thus, nothing really is.

These “afflicted” minds question everything. Not to arrive at truth, but merely to bathe in the excitation of the brain that accompanies the passion of wonder. They question the phenomena of the world, not in order to arrive at the truth underlying it, but merely to bathe in the intoxicating rush of wonder. We read that Descartes attributed this excessive wonder to people who have “no high opinion of their abilities.” What does this mean? It is a direct reference to what Descartes considers to be the supreme virtue, generosity, which is closely related to self-esteem. In generosity, one knows oneself to be free, and one has a firm resolution to use this freedom well. In such generosity, one has self-esteem, because one realizes that one already knows everything one needs to know to act well; one knows oneself to be free, and one has the resolution to use this freedom on the basis of what one knows. The perpetually astonished on the other hand, continually seek out new knowledge by being astonished at everything they come across, in a hopeless attempt to reach a point from which they could act with confidence. They feel themselves never enough, they never know enough. But in fact, the excessive astonishment is merely a postponement, it is a form of irresolution and anxiety. One prefers to be paralyzed by astonishment, than to calmly act on the basis of what one knows. Why? Because one believes confidence to be something to be reached in the future, when all the possible questions have been asked, when all the new experiences have been had, when all the knowledge has been gained. One thus fails to realize that one doesn’t need anything new to be confident, one merely has to recognize who one is; a free being with the power to act well on the basis of what one knows. One has to act, accept the consequences, and calmly adjust one’s actions when new knowledge is gained. Those with confidence, wonder at things to gradually increase their knowledge. Those who lack confidence, are astonished by everything and everyone, to flee themselves. We are confronted here with the core of Descartes’ ethics; that one needs only a very small amount of knowledge in order to act well; one needs to be conscious of one’s own self as a free human being with the power to decide on its own accord. All other knowledge is a useful addition, but one must be cautious of seeking out increasingly exotic knowledge, for one runs the risk of forgetting the most basic of truths in the process. And in a sense we are predisposed to seek out what is exotic and unfamiliar, instead of what is simple and easily recognized as true. For what is unfamiliar hits the brain with the intense feeling of astonishment, an addictive sensation that is not to be found in the recognition of the basic fact that one merely is, or that one has the power to act freely. Philosophy starts with wonder, evidently, but only in order to arrive at truth when the wonder has passed.

For Descartes, esteem and contempt are species of wonder. We can wonder at some thing’s significance and thus esteem it, but we can also wonder at something’s insignificance and thus feel contempt for it. But before these passions relate to objects outside of us, they relate to ourselves. We can have esteem for ourselves by realizing our significance, or we can have contempt for ourselves by feeling ourselves insignificant. Descartes relates the virtuous man of generosity to the passion of self-esteem, and the weak mind of perpetual astonishment to the passion of self-contempt. In generosity, the former realizes his own significance, for he realizes how free he is, and how much of an impact his own decisions have. The latter, is so convinced of his own insignificance, that he can feel nothing but contempt for himself, and he consequently flees into the world, being astonished by the significance of everything but himself. It is the passion with which we relate to ourselves, that conditions with what passion we will look at the world. With a healthy wonder, in order to strengthen one’s own power to act? Or with an astonishment born out of self-contempt, seeking merely to question everything, in order to not have to recognize the truth of what one is. As it said:

"If one supposes oneself inferior to things that come to be and perish and assumes oneself to be the most dishonoured and mortal of the things one does honour, neither the nature nor the power of god could ever be impressed in one's heart." (Plotinus, V.1.1.)

Does philosophy start in questioning? In the experience of wonder in which a thing asks of us to investigate it? Wonder evidently drags us onto the path of knowledge, but this is only half the story. Equally important is how and why one relates to this wonder. Does one use it to know oneself and nature, or to flee from nature and oneself? Does one use it to merely question ad infinitum, or does one use it to find truth on the other end? Does one question in order to flee from what one already knows, or does one question to recognize the existence of the one doing the questioning? Does one question to destroy, or does one question to build?

At first, we question everything unfamiliar, and bathe in the passion of wonder. But after a while, the more we find out, these things hardly impress us anymore, and we are content to recognize the truth.

“Eén gek kan meer vragen dan zeven wijzen beantwoorden kunnen.” For it is easy to question, but harder to find an answer. And there will always be more questions to ask, for some things cannot be questioned. There are more questions to be put forth for the existence of our own selves, than there are truths that show our own existence. The latter is simple and one, the former is exciting and many. And for those who are more attracted to quantity and pleasure than to truth, the path of the fool is tempting. All philosophy starts in wonder, but only bad philosophy never escapes from it. All philosophy starts with a question, but only good philosophy is able to offer an answer.

In Tarot, the fool is a card either numbered 0, or not numbered at all. It features as both the first and the last card of the tarot. As an archetype, it expresses new beginnings, the infinite potentiality of the child, questioning, innocence, freedom, and the desire to discover the unknown. The fool is the first card, for evidently, the journey of thought starts in the ignorance and wonder of the fool, and the desire to escape from it. A pure question-mark, and the desire to find an answer, wonder. Pure potentiality, absolute 0. But it would be foolish to admit that this is all there is to thought, for the fool is also the last card of the tarot. There is the fool, wondering at the world, and going on a journey to understand it, questioning as he goes along, and temporarily losing himself in the world. If all is well, he ends up on the other side; after having questioned the world, he is now ready to learn from what he has seen, and return back to himself. There are two fools; the everyday fool, who only questions and mocks, and the holy fool, who questions the world, in order to arrive at the truth. The tarot is not merely a journey of discovery, but also a journey of self-discovery. It is not discovery for discovery’s sake, but discovery in order to dis-cover what remains underneath all covering.

In the image of the fool, there is both foolishness, and wisdom. The innocence and foolishness of the beginning, and the simplicity of wisdom of the end. From the viewpoint of the former, the wise are fools for knowing so little. And from the viewpoint of the latter, the former are fools for wanting to know so much. There is no essential difference between the two fools, they are the same fool, only separated by the journey in between. But the first fool only questions, knowing nothing. The last fool, having already questioned everything, has now come to know himself. He has recognized that wisdom consists not in endless questioning, but in recognizing what should be questioned and what not, and in knowing, what is prior to and beyond any questioning. The wise fool can only smile at the childish fool, he has been there before, and knows that no answer can calm his thirst for questioning, he knows “there is no remedy for excessive wonder except to acquire the knowledge of many things and to practise examining all those which may seem most unusual and strange.” (Descartes, Passions of the Soul, Part Two, §76)

Those who take questioning to be all there is to philosophy, so gripped by wonder at what is new and interesting, fail to realize that there truly is something being questioned, and that there truly is someone doing the questioning. One loses oneself in the astonishment of the question, and forgets that there is something being questioned, and someone doing the questioning.

We used to wonder at how knowledge was possible, we used to question what structures were presupposed by knowledge. So fascinated by this questioning, we have forgotten that there is something being questioned. From a Platonic perspective; one becomes so addicted to what is out there moving in front of one’s eyes, that one forgets there is an eye doing the seeing, and that there is something being seen. There are always more things to be questioned, than there are things to be known. For the truth is often very simple, hardly leaving an impression in the brain. And as amphibian beings —mind and body, we are all predisposed to adore the complexity of bodily excitation, until we have seen so much, that we recognize the insignificance of it all. There is this descent into matter, into the addictions of the brain, until we are eventually catapulted back into what truly is. There is a function to this descent, in that “the experience of evil results in a clearer knowledge of the Good in those whose power is too weak to attain knowledge of evil prior to experiencing it.” (Plotinus, Enneads, IV.8.7. 15-17) Both socially and individually, both historically and eternally, the development of thought is such a descent. Are we ready to be pulled back, or have we yet to see how much our questions can destroy?

“Eén gek kan meer vragen dan zeven wijzen beantwoorden kunnen.”

Sources:

Michel Meyer. De la problématologie. Paris: PUF, 2008.

Cezary Wodzinski. Saint Idiot. Paris: Éditions de la différence, 2012.

Deleuze. Différence et Répétition. Paris: PUF, 1968.

Deleuze. Logic of Sense. Translated by Constantin Boundas, Mark Lester, and Charles Stivale. London: Bloomsbury, 1990.

Deleuze. Nietzsche et la philosophie. Paris: PUF, 1962.

Deleuze. La philosophie critique de Kant. Paris: PUF, 1963.

Descartes. The Philosophical Writings Volume 1. Translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Plotinus. Enneads. Edited by Lloyd P. Gerson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.