De Duivel heeft het vragen uitgevonden

The Devil invented questioning

This proverb means as much as that one shouldn’t want to know everything. Some stones are better left unturned, some questions are better left unasked. It is also said to someone when you want them to stop asking you questions.

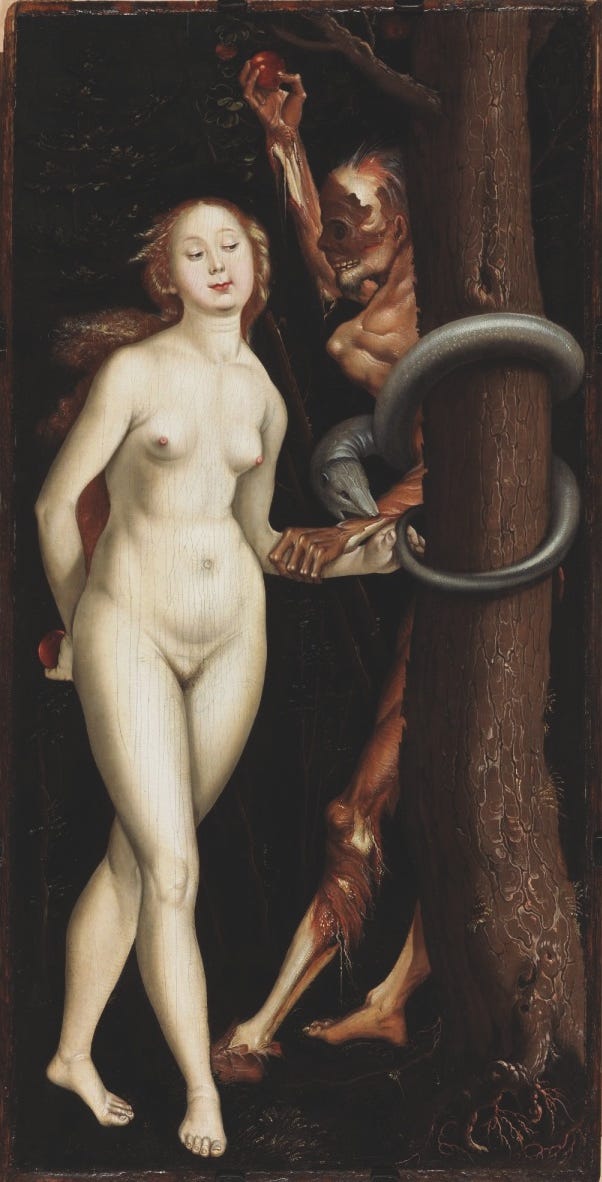

The proverb refers to Genesis III:1, where the first question in scripture occurs. Adam and Eve have received the rules of the garden. They know what to do, and are content in living as they know they should. But then, the serpent appears. We read:

“Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said to the woman, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat of any tree in the garden?’”

It is the first question that occurs in the Bible, and it is not just any question, but a question that will lead to the fall. Hence, not all questions are meant to be put forward, for we know to what a simple question can lead. It can be said that the emergence of questioning, this invention of questioning by the Devil, marks the first rupture of man with nature, or of man with God. An animal does not ask questions, but it does have problems, and solutions to these problems. It knows what to do to get food, it knows what to do to avoid being eaten. When an obstacle is blocking the way towards its food, it will be very inventive in overcoming this problem. But the animal does not question. The animal does not stop before the obstacle, and ask: what is this obstacle? It does not stop before its food, and ask: why do I even need to eat this food? Whatever presents itself to the animal, it never becomes ‘Vorhanden’. Note how in Genesis, it is said that “the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made.” The serpent is not like any other animal, for with the serpent arises the ability to question. Following the serpent, the human becomes the questioning animal. It is with him that life is no longer merely lived, but questioned.

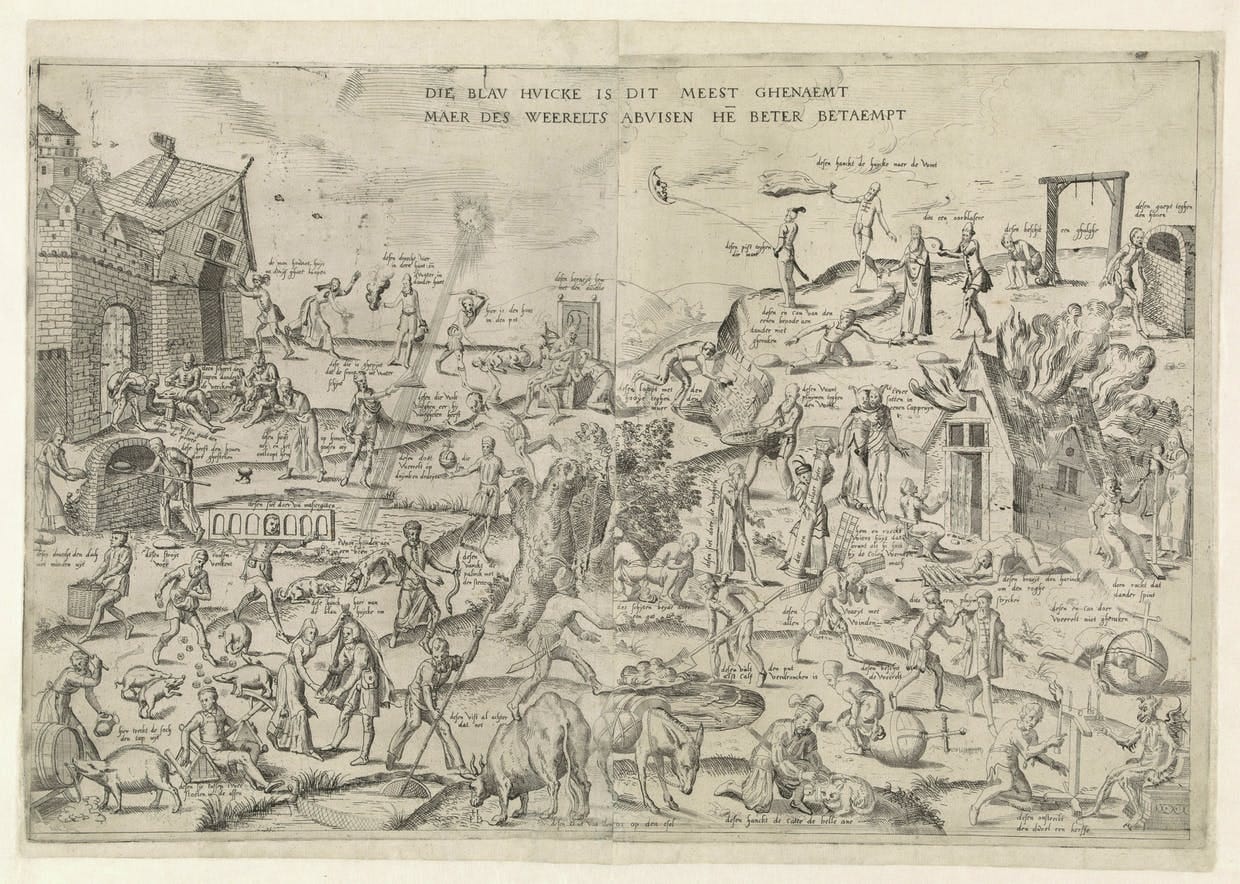

With the emergence of the question, we see not only the birth of knowledge, but also the birth of stupidity. From now on, the human can ask questions that lead him closer to the truth, but he can also ask questions that drive him deeper into ignorance. As it is said, asking the right questions already gives one half of the truth. Asking the right questions brings one closer to the truth, but likewise, asking the wrong questions drags one further away from the truth. To the questions we ask, we give answers. Answers that can be right, and thus give us truth. And answers that can be false, and thus bring us ignorance. With the birth of the question, the human can now ask stupid questions, and give stupid answers. The animal is prevented from such stupidity by its instincts. It cannot ask senseless questions, or give stupid answers. For there are no questions asked, and no answers given. There are only problems given by nature, and solutions instinctively undertaken. The instincts of the animal prevent it from making mistakes, or from saying insignificant things. There is no gap between problem and solution, a gap in which the human stands still, and asks the question. A gap, that opens up the possibility of wisdom, but also the possibility of folly.

In this gap, where the object ceases being Zuhanden, and becomes Vorhanden, theory emerges. All the splendours of civilization and science, come from this all too human capacity to question. ‘What is this?’, ‘Of what is this composed?’, ‘How do I make this tool better?’, ‘How?’, and most importantly, ‘Why?’

We owe much to the question. What is ‘reason’, but the ability to question things, to ask how they are composed? But we do not only question things, we also question people, ideas, opinions, rules, etc. In short, we question manners of living. As the serpent, and consequently Eve, ask if it really is important to not eat from the tree in the garden.

No question is innocent, for it sets us on the path of action. The moment we start asking if we should not eat from the tree, is the moment the possibility arises that we will eat from the tree. When you are running in the woods, and getting tired, the moment you ask yourself “should I not stop?”, is the moment you have started giving up. Hence, not all questions should be asked, lest the question drives us to undertake actions that we will regret.

As much as asking questions is what makes us human, this human capacity should not be unfolded too recklessly. For, ‘de Duivel heeft het vragen uitgevonden.’ There are questions that are better left unasked, and as much as our ability to pose questions marks our reason, it can also be evidence of our folly. Let me explain by way of Descartes’ philosophy.

No philosopher expresses more this human capacity to question than Descartes. As is well-known, in his Meditations, Descartes proceeded to apply himself like no other to the complete demolition of his opinions. He wanted to question everything, to doubt everything, so that he might find certainty. But why did Descartes wait until he was forty-one years old to undertake this most radical questioning? Because for the first time in his life he had no other obligations, no more important tasks to complete. For the first time, Descartes could completely give himself over to ‘meditation.’ These are not mere biographical circumstances. These are important remarks that lead us to the core of the Cartesian spirit. In the First Meditation, Descartes explains why he is able to question so relentlessly. We read:

“For indeed I know that meanwhile there is no danger or error in following this procedure, and that it is impossible for me to indulge in too much distrust, since I am now concentrating only on knowledge, not on action.” (Descartes, Meditations. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1998).

The heights of thought will be reached by an unrelenting questioning. But, we must make sure that this questioning remains only on the level of theory, and isn’t recklessly applied to the domain of action. It is because Descartes is not concerned with acting, that he can question so radically. Why? To act, one needs a sure basis from which one can act. In order to act on a choice, one needs to know or believe that this choice is best. Thus, one cannot be stuck in absolute doubt, or in complete epoché of all beliefs. The man of action cannot be wasting his time questioning everything, for he will become unable to act.

There is a certain stupidity to questioning, when instead one should be acting. We can think of a soldier undertaking a Cartesian doubt in the midst of battle, or asking whether there really is a difference between nature and artifice, when the products of artifice are killing us. There are times, when questions should not be asked, for danger of them leading to reckless actions. Or perhaps even worse, for danger of us not acting at all. This is why one should not listen to philosophers too much, those artists of the question. At least, when these philosophers think, in separation from life.

There are times when asking a question is not warranted, but there are also times when asking the same question is warranted. There is a stupidity proper to asking the ‘right’ theoretical questions, in the wrong context. But even in the domain of pure philosophy by itself, in the domain of ‘meditation’, there is a certain stupidity to asking too many questions.

In Descartes’ dialogue La Recherche de la Vérité, a person explains the Cogito argument to someone else. I can doubt everything, but I cannot doubt that I am doubting, thus, I exist. I doubt, I am. Someone else in the dialogue does not accept the argument, not believing it proves the certainty of our own existence. He objects; “but what it means to doubt? What it means to exist? Do you know this?” Descartes responds: “I don’t think I’ve ever known someone to be so stupid, that he first needs to know what existence is, before he can conclude that he exists.” This person is so well-developed in his human capacity for questioning, in his reasoning, that he fails to accept even the most obvious truths. So smart, that he doesn’t even know if he exists. ‘de Duivel heeft het vragen uitgevonden.’

Let me give another example, all too close. These days, governments around the world have become very keen on taking away essential freedoms from their citizens. Freedom to do with your own body as you please, freedom of association, etc. Citizens protest, with good reason, that their freedom is being eaten away. But what do you hear from the ‘thinkers’ of society? You hear: “But what is freedom? Do you know this?”, “You protest for ‘freedom’, but is there even such a thing as freedom?”, “You want bodily autonomy, but what is autonomy?” In a philosophy lecture, asking these questions is evidence of a healthy spirit. But when your freedoms are being taken away, asking these questions speaks only of one’s own stupidity, as Descartes would say. It is no sign of the well-thinking to need to have a clear definition of what freedom is, before one can conclude that one is a free man or a slave.

The form of these questions —of the stupid man in Descartes’ dialogue, and of the un-free of today—, is eerily similar to the form of the serpent’s question. We read again:

“And he said to the woman, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat of any tree in the garden?’”

These are not questions like the simple questions with which we investigate the world: “what is the speed of light?” or “where is Rome located?” The serpent’s question is a question that attempts to make the other doubt one’s own reality. For Eve, it is evidence itself that she should not eat from the tree. It is so evidently true, that the question doesn’t even arise. She knows it in her flesh. But still, she is deceived. For it is easy to question, but harder, to know why one shouldn’t always question. Regard the ease with which the serpent is able to deceive Eve. The serpent only needs to mention that Eve won’t die from eating the fruit, that she will become smarter, and that the fruit tastes good. Unprotected by instinct, humans are this easily deceived.

Eve knows what God told her. It is beyond questioning. But the serpent invites her to question her own evidence. “Did God really say this? You might think you heard this, but can you really trust yourself as to if you really heard this? Can you really trust your own ears, your own eyes?” “You feel yourself to be free, but are you really? Maybe, your brain is just deceiving itself? Maybe, you are just a victim to ideology?” The Devil invented questioning, and in questioning, he enacts his deception. A crucial part here, is that the question aims to take away Eve’s confidence in her own senses, and in her own thought. I heard what God said, but ‘what do I know.’ We can only be deceived, if we open ourselves up to being deceived. And by taking away our confidence in ourselves, the Devil’s question opens us up for deception.

Is it not telling, that after eating the fruit, Adam and Eve feel shame for the first time?

Those who have not been deceived by the philosophers, know that they themselves exist. Those who have not been deceived, know that they are free. They feel themselves free, and they feel it when they are becoming slaves. “But do they really?”, This is the Devil’s question. It attempts to make you question what you know to be beyond questioning. It makes you question, what you know in your flesh to be true. It attempts to take away your confidence in your own thought, in your own truth. Disguised as reason, it takes away all you hold most dear: your self, and your freedom.

De Duivel heeft het vragen uitgevonden.