“Do you also think about the matter carefully: it is not what it seems to you. (You say) I wear a cloak now and I shall wear it then: I sleep hard now, and I shall sleep hard then: I will take in addition a little bag now and a staff, and I will go about and begin to beg and to abuse those whom I meet ; and if I see any man plucking the hair out of his body, I will rebuke him, or if he has dressed his hair, or if he walks about in purple—If you imagine the thing to be such as this, keep far away from it : do not approach it : it is not at all for you. But if you imagine it to be what it is, and do not think yourself to be unfit for it, consider what a great thing you undertake.”

(Epictetus, Discourses 3.22.9-12 ‘On Cynicism’.)

In this article, I explain the philosophical method of Diogenes the Cynic. This article is intended as a follow-up post to my previous article: ‘Socrates gone mad: an introduction to the philosophical radicalism of Diogenes the Cynic.’

I recommend you read this article first to get a full understanding of today’s text, especially if you are unfamiliar with Diogenes.

I. A Cynic philosophy?

In our previous episode, we introduced Diogenes the Cynic. It is now time to take a closer look at his actual philosophy. A strange task, the undertaking of which might seem pointless. For as we have seen, Diogenes has no ‘philosophy’ in the ordinary sense of the word. There are no texts of his that remain, there are no lists of his views on things, and there are no metaphysical treatises. In short, there is no clear doctrine ascribed to him. All we have are anecdotes of Diogenes interacting with people on the streets of Athens, witty remarks, scandalous behaviour, but no real ‘philosophy.’ Yet, if we read these fragments, it is clear that there must be some theoretical framework behind them, even if it was never written down or spoken aloud. There must be a whole of thoughts, that influenced Diogenes’ often shameful behaviour. There must be some philosophical principles that determined Diogenes’ life. And it is these principles that we are looking for here. When Diogenes is seen walking around with a lamp during broad daylight, searching for a man, but nowhere finding one, this must mean that he has an idea of what a man is supposed to be. In this way, by reading between the lines, we can get a grasp of Diogenes’ philosophy.

It might seem, that this pursuit for the principles of Diogenes’ philosophy is very un-Cynic, for the Cynics were very much anti-theoretical philosophers. When people asked him what books they should read, Diogenes scolded them, saying that practice is more important than theory.

And indeed, practice is more important than empty words. But perhaps, if we have the principles written down, it will be easier to follow through.

Throughout the history of philosophy, not everyone has found it valuable to seek for the philosophy of Diogenes and other Cynics. Hegel, the great German philosopher, believed that: “There is nothing particular to say of the Cynics, for they possess but little Philosophy, and they did not bring what they had into a scientific system.” For Hegel, the Cynics are not worth speaking about, for there is nothing to say about them. In a sense, he is right, for there is no clear doctrine to be ascribed to Diogenes and other Cynics. For Hegel, there is no system in the Cynics, and thus there is no philosophy. Hegel ends his discussion of the Cynics by saying that they fully deserved to be called dogs, “for the dog is a shameless animal.” And he believed that the “independence of which the Cynics boasted, is really subjection.” (Hegel, Lectures on the history of philosophy, 479-487.)

Hegel is right, in that there is no clear system of philosophy to be ascribed to the Cynics. But this absence of a system, is itself a part of the Cynic philosophy. Hegel, the man who believed that freedom consisted in a willing subjection to the State, and who thought that system is the same as philosophy, could never understand this. And thus, we will not listen to Hegel. We will endeavour to outline the philosophy of Diogenes, the dog of Athens, for whom philosophy has nothing to do with system, the man who fought all subjection, however much it sells itself as freedom. To engage with Diogenes and the Cynics, we have to engage with the possibility that there is a different way of doing philosophy. A way of doing philosophy that has nothing to do with system or text. And only if we are willing to entertain this possibility, will our engagement be fruitful.

Today, I will look at what Diogenes took philosophy to be, and what he took its method and task to be. In a coming article, I will explain and summarize the core principles of Diogenes’ philosophy.

II. The model of the Cynic sage

Something peculiar about Diogenes is the manner in which he related himself towards his fellow men. Diogenes sought the life of philosophy, that is, the life of the sage. Leading a life of ‘askēsis’, the root of our word asceticism, meaning literally ‘training’. He sought a life devoted entirely to the training of body and mind, to achieve freedom and independence. When we think of such a life, we often conjure up images of a wise hermit living far away from society, living in a cave or on a mountaintop, contemplating the universe in silence. But this was not how Diogenes lived, far from it. Diogenes lived as close as possible to other people. He would sleep in the most crowded marketplaces, visit the Olympic games, and seek out conversation with his fellow Athenians. For as much as Diogenes saw himself as a sage, independent vis-à-vis his surroundings, he didn’t just want to abide in this independence. He had found peace within himself, and now he saw it as his task to show others that they too could find this peace. When someone asked Diogenes; ‘but why do you live among us, if you think we are so wicked?’, our philosopher replied:

“But a doctor, being a man who is responsible for bringing people to good health, does not carry out his business among those who are healthy.”

(Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §63, 20)

He thought of himself as a doctor, who had to live close to his patients. If you recall our previous post, Diogenes once went to the Delphic Oracle asking for direction in life, when the Oracle answered that he should “deface the currency.” Once he was a philosopher, Diogenes took this to mean that he should deface the customs, norms, and false opinions of the masses, so as to lead them to a life of virtue and happiness. There is a missionary character to the life of Diogenes. As much as he saw himself as separated from the masses, he endeavoured to be with them. And as much as he shamed and ridiculed his fellow men, he loved them. And it was precisely because he loved them, that he was so hard for them.

III. A veil of madness

The Cynic philosophy was rather dark in outlook. Diogenes thought that most people are wicked, and do not even deserve to be called human. And Diogenes would often say so directly, claiming that there are no men to be found in Greece, or referring to his fellow citizens as less-than-human. But as much as the Cynics thought this, they strained themselves to put the masses on a better path. And this could only be so, because they believed in the innate goodness of mankind. Every man has in him a spark of reason, a part unaffected by vice, a part to which the Cynic seeks to break through, in order to activate this part, and start a process of change.

This is the basic model of the Cynic view of the world; the masses live in wickedness, and through direct speech and action, the philosopher transforms the masses.

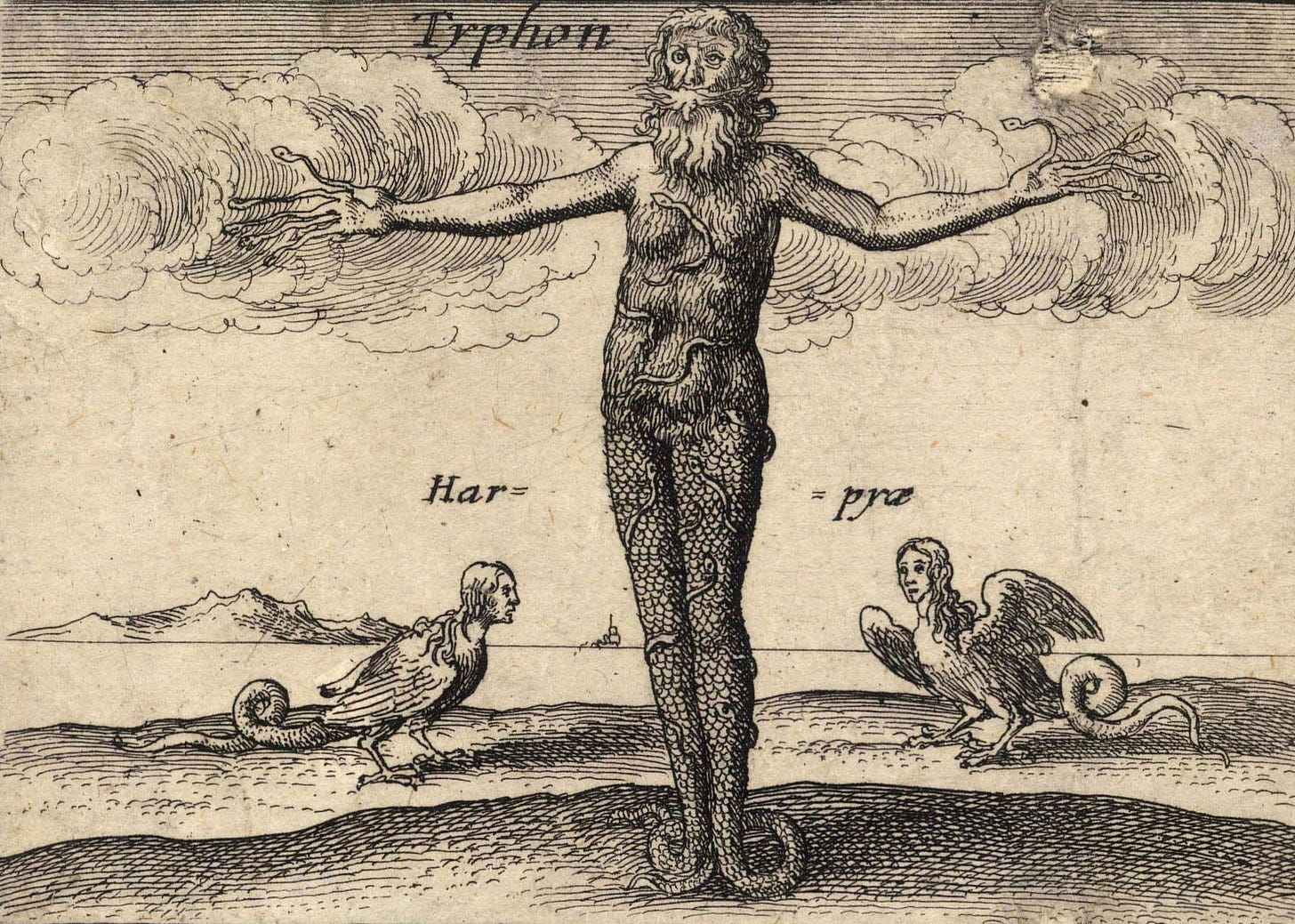

An important notion here is Typhos (Τυφώς). For the Cynics, typhos signifies this veil of ignorance and wickedness that clouds people’s judgement, and makes them live a less-than-human life. In their deepest essence, everyone is good and capable of a virtuous life, for otherwise the Cynic philosopher wouldn’t attempt to change them. But then why doesn’t everyone live such a ‘good’ life? Because of ignorance, because everyone is trapped in typhos; a cloud of darkness that makes them act wrongly. The task of the Cynic philosopher is to pierce through this veil, thus showing the people the wickedness and stupidity of their behaviour, and urging them on to a life of virtue. The Cynics attempted to pierce this veil through ‘parrhesia’(παρρησία): truthful, free, and direct speech. Saying it how it is. In word, and in action. By calling the people out for their wickedness, by simply hitting them with a stick, or by urinating on their possessions. When asked what the finest thing of all is in life, Diogenes replied: “plain speaking”(parrhesia). (Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §222, 50)

Whereas philosophers like Socrates or Plato sought to convince people through extended argumentation and dialogue, the Cynics preferred simple and short words, ‘parrhesia.’ Someone lived a life of vice? Socrates might try to convince this person to better his ways by carefully speaking to him with well-crafted arguments. But Diogenes would simply call the person out for his behaviour, thus trying to shock him into virtue. Someone lived as a glutton? The Cynic wouldn’t try to convince him that this was bad, but would just call him a fat pig.

Typhos means as much as ‘smoke’, ‘veil’, ‘mist’, or ‘cloud’. And the Cynics used it to signify the cloud of unknowing in which most people live, like a veil of madness that prevents them from seeing clearly. Blinded by this veil, people value things that have no real value, but care not for what is actually valuable. They live a life chasing pleasure, but care not for chasing virtue. They care for their possessions, but not for their soul. They love what they have, but not what they are. They seek endless amounts of money, but not true wealth, which consists in self-sufficiency.

“When asked who is rich among men, he [Diogenes] replied: ‘He who is self-sufficient.’”

(Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §17, 12)

IV. Typhos and Zeus

Why are people so misguided? Because they are blinded, because they live under the grip of ‘typhos’. To grasp the true significance of the concept, we must look at its origin in Greek mythology.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, we read that Typhon or Typhoeus was a monster born of Tartarus and Gaia:

“The huge Earth bore as her youngest child Typhoeus, being united in intimacy with Tartarus by golden Aphrodite. His arms are employed in feats of strength, and the legs of the powerful god are tireless. Out of his shoulders came a hundred fearsome snake-heads with black tongues flickering, and the eyes in his strange heads flashed fire under the brows; and there were voices in all his fearsome heads, giving out every kind of indescribable sound. Sometimes they uttered as if for the gods’ understanding, sometimes again the sound of a bellowing bull whose might is uncontainable and whose voice is proud, sometimes again of a lion who knows no restraint, sometimes again of a pack of hounds, astonishing to hear; sometimes again he hissed; and the long mountains echoed beneath. A thing past help would have come to pass that day, and he would have become king of mortals and immortals, had the father of gods and men not taken sharp notice. He thundered hard and stern, and the earth rang fearsomely round about, and the broad heaven above, the sea and Oceanus’ stream and the realms of chaos. Great Olympus quaked under the immortal feet of the lord as he went forth, and the earth groaned beneath him. A conflagration held the violet-dark sea in its grip, both from the thunder and lightning and from the fire of the monster, from the tornado winds and the flaming bolt. All the land was seething, and sky, and sea; long waves raged to and fro about the headlands from the onrush of the immortals, and an uncontrollable quaking arose. Hades was trembling, lord of the dead below, and so were the Titans down in Tartarus with Kronos in their midst, at the incessant clamour and the fearful fighting.

When Zeus had accumulated his strength, then, and taken his weapons, the thunder, lightning, and smoking bolt, he leapt from Olympus and struck, and he scorched all the strange heads of the dreadful monster on every side. When he had overcome him by belabouring him with his blows, Typhoeus collapsed crippled, and the huge earth groaned. Flames shot from the thunderstruck lord where he was smitten down, in the mountain glens of rugged Aïdna. The huge earth burned far and wide with unbelievable heat, melting like tin that is heated by the skill of craftsmen n crucibles with bellow-holes, or as iron, which is the strongest substance, when it is overpowered by burning fir in mountain glens, melts in the divine ground by Hephaestus’ craft: even so was the earth melting in the glare of the conflagration. And vexed at heart Zeus flung Typhoeus into broad Tartarus.

(Hesiod, Theogony, 27-28.)

Typhon had a hundred snake-heads with black tongues, and his eyes flashed fire. Out of each head came indescribable and hellish sounds. Typhon was so powerful, that with his earth-shaking force, he could have become the king of both mortals and immortals. But Zeus, father of men and gods, had taken notice of Typhon. With his thundering blows, Zeus fought Typhon. And leaping forth from mount Olympus, Zeus scorched the head of Typhon with lightning. And so, Typhon was defeated, and cast down into Tartarus. With this myth in mind, the Cynics used the notion of typhos. Zeus, signifying the reasonable and orderly principle of Divinity, and Typhon signifying darkness, disorder, and the cloud of unknowing, that when uncontrolled by Zeus, can plunge the cosmos into ruin.

In this way, typhos came to stand for that principle in everyone’s soul that leads to wickedness and misery. Typhos: the source of spiritual darkness. And Zeus: the reasonable principle in all of us, that can fight our weaknesses born from typhos. Before the mythical Typhon was laid to rest in Tartarus, he bore many other monsters as his offspring. According to Appollodorus, one of these was the Nemean lion. This lion was a monstrous beast, said to have been impervious to human weaponry. No sword or arrow could pierce its golden skin. However, it was finally slain by Heracles, who strangled the lion with his bare hands.

V. At war with ignorance

All these things are important to understand the Cynic notion of typhos. For the Cynics often compared themselves to Heracles. Diogenes Laërtius writes that:

“He [Diogenes the Cynic] thus maintained that his way of life was of the same stamp as that of Heracles, in so far as he set freedom above all else.”

(Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §105, 30)

The Greek hero stands for all that is noble of character: virtue, self-control, courage, strength, freedom, and self-sufficiency. And like Heracles waged war against evil monsters, the Cynics waged war against the wickedness of the human soul. Through the practice of virtue and courage, they attempted to set humanity free from the cloud of darkness that drags it down. Like Heracles fought the offspring of Typhon, the Cynics waged war against the offspring of human ignorance, against the behaviours born from a life controlled by typhos.

Typhos occurs most notably in the verses of Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes. In one of these verses, Crates speaks of a mythical island-city, ‘Pera’, in which there is no evil, and everyone lives a simple life in accordance with virtue, free from human stupidity and madness. Crates says that this island is surrounded by a “wine-dark sea of folly”. For this sea of folly, “typhos” is used.

“There is a city, Pera, in the wine-dark sea of folly,

Fair and fat, though filthy, with nothing much inside.

Never does there sail to it any foolish stranger,

Or lewd fellow who takes delight in the rumps of whores,

But it merely carries thyme and garlic, figs and loaves,

Things over which people do not fight or go to war,

Nor stand they to arms for small change or glory.”

(Crates of Thebes, In ‘Diogenes, Sayings and Anecdotes, §439, 94)

Although it is said that Crates wanted to actually found such a city, a sort of ‘(Cynic) philosophers paradise’ free from the ills of normal society, this verse should be taken mostly symbolically. Through self-discipline and courage, the Cynic philosopher attempted to make his own soul a place like Pera, a fortress, self-sufficient, unaffected by the madness of the wicked masses that surround the philosopher. For the Cynics, typhos stands for the ignorance of humanity that prevents it from reaching what it desires most of all: happiness. Deceived by their senses to pursue pleasure over virtue. Urged on by their selfishness to engage in senseless conflicts, instead of bettering themselves. Typhos stands too for the web of corruption and bureaucracy, that all too often sickens institutions and communities. The web of senseless rules, customs, and behaviours that crushes people’s freedom, kills their spirit, and plunges them into sin. The cloud of stupid beliefs, that makes them live in fear. The veil of childish desires, that makes them renounce their true purpose. For the Cynics, this is all typhos. But it need not be this way, the Cynics say. For we can, with the power of Zeus (who symbolises reason), and the courage and self-control of Heracles, fight the demonic force of typhos. We can make our souls a stronghold against wickedness, a place safe from the influences of our surroundings, that invite us to renounce reason and follow our misguided desires, that invite us to practice weakness, instead of strength. A life lived under typhos is an unconscious condition in which the human has no control over himself, but is controlled by his surroundings. In the grip of typhos, we unthinkingly repeat the opinions of our society, and we blindly follow our desires, whatever vice they might lead us into. The Cynics invite us to step out of this slave-like existence, to think, to reason, to break the spell of typhos, and to take control over our own direction in life. They do this through ‘parrhesia’, honest and direct speech. But also through action: Diogenes hitting people with his stick, or walking backwards in the streets to show that the people are taking the wrong direction in life.

Through this direct form of philosophy, the Cynic tries to break others out of the matrix of typhos. It is the notion of typhos, that explains why the Cynics prefer ‘parrhesia’ over lengthy speech. If a person is under the grip of typhos, he is blinded, and cannot reason properly. Thus, offering him arguments or engaging in lengthy dialogue with him, leads nowhere. What needs to happen is a rupture, a violent break, a painful word or an embarrassing confrontation, that breaks through the spell of typhos.

VI. The cave of typhos

To explain why the Cynics prefer parrhesia over lengthy dialogue, we must look at Plato’s famous cave allegory. In this allegory, there are people chained to the wall of a cave. They have lived this way all of their life. Chained as they are, they face a wall. On the wall there are shadows, projected onto the wall by all sorts of objects moving in front of a fire located behind them. The people don’t see these objects, nor do they see the fire. All they see are the shadows. And consequently, they take these shadows to be reality, for it is all they have ever known. One day, one of the people is freed from his chains and forcefully dragged away by a foreigner, he is dragged past the fire that is the source of the shadows, and out of the cave, into the light. What is interesting here is that the person experiences this as very painful. He has never seen direct sunlight, and it brutally hurts his eyes. And at first, he takes what he comes to see as illusory, as only images. He wants to go back to watching the shadows, which he still takes to be reality.

“-And if someone compelled him to look at the light itself, wouldn’t his eyes hurt, and wouldn’t he turn around and flee towards the things he’s able to see, believing that they’re really clearer than the ones he’s being shown?

-He would.

-And if someone dragged him away from there by force, up the rough, steep path, and didn’t let him go until he had dragged him into the sunlight, wouldn’t he be pained and irritated at being treated that way? And when he came into the light, with the sun filling his eyes, wouldn’t he be unable to see a single one of the things now said to be true?”

(Plato, Republic, VII, 515e)

Eventually the man’s eyes adjust to the sunlight, and he realizes that true reality is outside of the cave, and that prior to this new experience, he took for reality what was merely shadow. He decides to go back into the cave to tell his chained friends about the real world. But when he arrives in the cave, and starts telling his friends about what he has seen, they take him for a fool. They laugh at him, for from their point of view, the man is only talking about imaginary stuff. And the interesting thing is that, from their point of view, they are right. For their reality consists only of these shadows on a wall. To them, the man is talking about imaginary stuff. Wouldn’t they be fools to believe the reality of something that they have never seen themselves?

The point of this allegory, and what is of relevance here, is that Plato shows that there is no point in trying to convince the cave dwellers. They cannot be convinced through words and arguments. The only thing that can help them is to also drag them out into the sunlight. They cannot understand the truth, if they are not also confronted with it. Like the people in the cave allegory are trapped in a cave watching shadows, the Cynics believe that most people live similarly, be it that the cave is typhos. And living in typhos, knowing only the illusory understanding it offers, they cannot be reasoned with. And thus, they must be dragged into the sunlight. And parrhesia is the tool. No extended dialogue or argumentation, but short and violent words and actions.

According to the Cynics, there are two roads to a philosophical life of virtue. There is the long road, the road of careful dialogue, argument, and examination. And there is the short road, the road of direct confrontation. If, as non-philosophers, we live in the cave, and someone comes to visit us, trying to convince us of a world where there is a sun. He can do two things, he can undertake the difficult task of trying to convince us. Or, he can break our chains and drag us into the sunlight. The Cynics believe that the second road is the most correct, and guarantees the most success. For doesn’t Plato himself say, that it is pointless to argue with the cave-dwellers? This is the Cynic critique of Plato and Socrates, they think that words will save the world. The Athenian citizens, living an unexamined life of vice, should not be reasoned with. Rather, they should be shocked into virtue. They must be woken up, the spell of typhos must be broken. In Plato’s Meno dialogue, Socrates is compared to a torpedo fish who stings people with his words, perplexing them, and forcing them to examine themselves. It is this aspect of philosophical speech that the Cynic stress to a radical degree.

In choosing the short road of parrhesia over the long road of dialectics, the Cynics once again compare themselves to Heracles. In the story of the Greek hero, it is said that the young Heracles, contemplating what he is to do with his life, is visited by the personifications of Vice and Virtue; Kakía and Areté. At first, Vice speaks to Heracles, telling him that if he follows her, he will be granted an easy life, full of pleasure, and with no hardship. Secondly, Virtue speaks, suggesting that Heracles follow her. If he does, he will be granted immortal glory and true happiness and fulfilment. Not a happiness of pleasure, but of the soul. But the path of Virtue is hard and long, and Heracles will have to suffer much along the way. However, the rewards are more valuable than anything Vice could offer. Of course, as further legend makes clear, Heracles chose the road of Areté. The Cynics use this tale to show that each and everyone of us has a choice in life; an easy life of pleasure, or a hard life of virtue. We can remain in the cave, amusing ourselves by watching shadows, pleasantly bathing in typhos. Or, we can suffer the pain of the burning sunlight, the pain of leaving what is familiar, and discover true happiness, which consists in living in truth. The Cynics see themselves as undertaking this Heraclean task; to choose the hard road to virtue for themselves, but also to act as guardians for others, dragging them onto the path of virtue. For most people are too weak, and like the cave dweller in Plato’s allegory, they need someone to drag them onto the road of truth. It is a painful road, but the only road that leads to the destination: freedom.

VII. Dragged into the sunlight

To drag the people out of the cave of typhos, by the power of reason, and the strength and courage of Heracles. This is what the Cynics see as their God-given task. And they believe their task can be achieved. They believe, that everyone can make a conversion towards virtue. Like everyone in Plato’s cave can be converted to the light, if only someone were to break their chains and violently drag them into the sunlight. There is no need for someone to have a certain level of intelligence, to understand the benefits of a life of self-control and virtue, they need only see and feel the light of virtue. And hence, the model of the Cynic sage is not the solitary wise-man living alone on a mountain. Rather, he is the foreigner of Plato’s cave allegory; living in the light of the sun, but going into the cave to rescue people, to drag people into the light.

Sources:

Diogenes the Cynic. Sayings and Anecdotes. Translated by Robin Hard. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Epictetus. Discourses. Translated by George Long. New York: Appleton, 1904.

G. W. F. Hegel. Lectures on the History of Philosophy vol. 1. Translated by E. S. Haldane. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963.

Hesiod. Theogony and Works and Days. Translated by M.L. West. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Plato, Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper. Cambridge: Hackett, 1997.