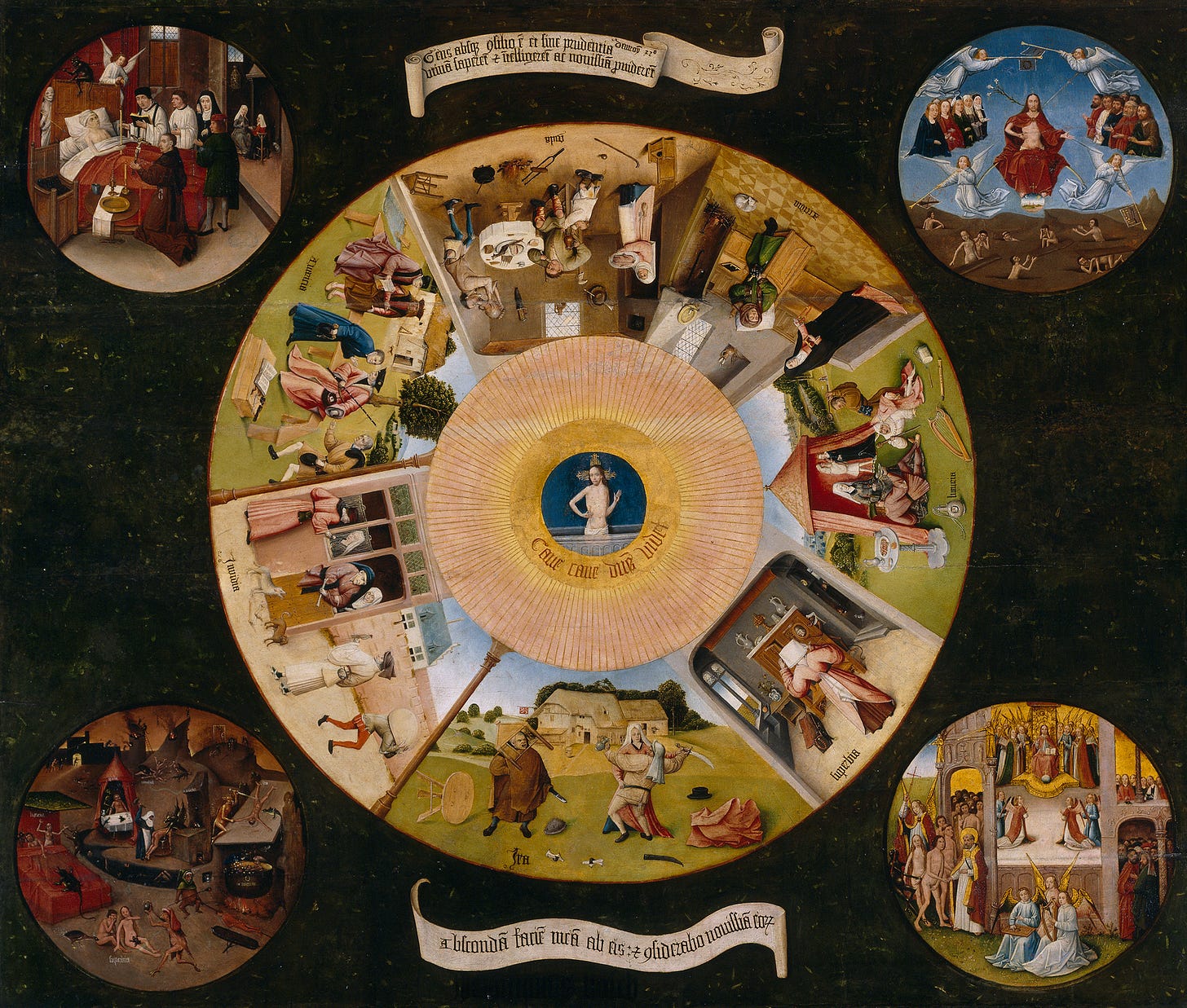

Reading through a book on Hieronymus Bosch, I came across this passage:

“The tendency to interpret Bosch’s imagery in terms of modern Surrealism or Freudian psychology is anachronistic. We forget too often that Bosch never read Freud and that modern psychoanalysis would have been incomprehensible to the medieval mind. What we choose to call the libido was denounced by the medieval Church as original sin; what we see as the expression of the subconscious mind was for the Middle Ages the promptings of God or the Devil.” (Walter S. Gibson, Hieronymus Bosch. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973. p12. Italics my own)

Regarding this, some thoughts came up with regard to Cartesian dualism and the idea of a ‘subconscious.’ I share them here. I will probably depart from the letter of Descartes’ text, and seek merely to use some ideas to explore why one would not accept the idea of a ‘subconscious mind’, an idea so obvious to the modern mind. We find it hard to believe that one wouldn’t believe in subconscious forces determining our thoughts and actions, but this wasn’t always the case, why? Let us speculate.

I. (un)conscious thought?

With Descartes, all thoughts, feelings, desires, etc., are conscious. There is a consciousness, an I, a mens, ‘Cogito’, to which thoughts, feelings, and desires appear. And thus, all these thoughts, feelings, desires, etc., are conscious. I would not know of the existence of a thought if I didn’t think it. And this is what mens, mind, means by essence; this power to be conscious of thoughts, feelings, desires, etc. The mind is this power to be conscious of thoughts, feelings, etc., and the mind is this power to consciously will or not will these thoughts and feelings of which it is conscious. I am, and to I appear thoughts and feelings. I am, and I have the power to doubt, believe, accept, renounce, etc, the thoughts, feelings, and desires that appear to me.

Later, in Leibniz perhaps first clearly established, we find the idea that not all thoughts or feelings are conscious. There are ‘unconscious thoughts’, that are like the building blocks of conscious thought. There are little unconscious thoughts and feelings, ‘perceptions’, that mingle together, and when they reach a certain threshold of intensity, they start to form conscious thoughts, feelings, etc. We read in Leibniz:

“noticeable perceptions arise by degrees from ones which are too minute to be noticed.” (Leibniz, New Essays on Human Understanding. Preface, 57).

Now, for Descartes, the idea of such ‘unconscious thoughts’ that are the building blocks of conscious thoughts, is a very uncertain idea. For two major reasons:

When we speak only in terms of absolute certainty, consciousness cannot be the result of anything, but is itself the absolute pre-condition for anything appearing. It is because I am conscious, that thoughts, feelings, desires, etc. can appear to me, can come to my conscious awareness. Hence, the postulation of unconscious thoughts, is wholly a postulation done by consciousness. And thus, these unconscious thoughts cannot be said in certainty to be prior to conscious thought.

Michel Henry writes that we can reject a philosophy of consciousness verbally, but it is always on the basis of consciousness that a subconscious is postulated to supposedly dethrone consciousness qua priority. (Henry, Généalogie de la psychanalyse, 344). This is evident. If one wants to say that unconscious thoughts are prior to and constructive of conscious thoughts, one has to be willing to take a leap. One has to be willing to say that what is theoretically discovered by consciousness, can be prior in reality to consciousness. This is a leap, that Descartes is not willing to take. He is willing to speculate about it, he is willing to take the leap speculatively, but he will never absolutely dethrone the priority of consciousness. He is too obsessed with certainty to do this.

In the idea of unconscious thought, a strange duplication happens. It is extremely probable that there are processes of which we are not aware, that influence our feelings and thoughts. See Descartes’ mechanical works on man, or the Passions of the Soul. But to say that these forces or processes are ‘thoughts’, that they are like miniature thoughts and feelings that are the building blocks of conscious thought, this is stupid from the cartesian perspective that sees a distinction between conscious thinking and whatever might be postulated to happen outside of consciousness. All thought is necessarily conscious. Have you ever experienced a thought or feeling of which you were not conscious? To talk of ‘unconscious thoughts’ that control my thoughts, this is purely wild speculation that applies a quality (thought), to a domain in which it is impossible to know whether ‘thought’ exists there. But in doing so, there ceases being an essential difference between conscious thought and whatever is out there and could be the cause of my thoughts, feelings, etc. It is postulated to all be the same stuff, ‘thought’, even though I can only know of thoughts consciously. How can I say, with certainty, that what is ‘out there’ is thought? Again, one has to take a speculative leap.

Now, in postulating that there are ‘unconscious thoughts’, something very important has happened, seemingly unnoticed; ‘mind’, and all the qualities that belong to mind, are applied to the domain of which we are not conscious. Why? Because thought by definition pertains only to mind. What is mind according to a Cartesian? It is that force that we are that is conscious and able to will, or refrain, from willing whatever it is conscious of. A desire arises, and I as mind, am able to go with this desire, or refrain from it. The mind is a power to choose. We have all these thoughts, feelings, and desires, but because we are a mind that is conscious of them, we can choose to accept or reject a thought, we are able to refrain or accept a desire, etc. But when thought, which in the philosophies of the Cartesians is necessarily linked to this power of mind, comes to apply to that of which we are not conscious, a ‘subconscious mind’ is postulated. In different terms, an unconscious consciousness. For Descartes, a paradox. For Leibniz or Spinoza, simply how they conceive of God; an infinite consciousness of which our particular consciousness is not conscious, but of which we are an expression, an expression passive by itself. It might seem like we are a mind, but in reality, we are only an idea in the mind of God. We do not think, we are being thought. As a result, we have the familiar doctrines that still taint our minds today, saying that we only seem to be free from our particular perspective, but if we were to look at ourselves from the mind of God, we would see that we are completely determined.

In this shift from conscious thought to unconscious thought, this power of mind to choose, to determine which thoughts, feelings, or desires, are accepted or doubted, chosen or refrained from etc, is lost to us, and comes to belong to the ‘subconscious mind.’ And the ‘power’ that consciousness had vis-à-vis the thoughts, feelings, desires, etc., is completely gone. Where is this power now? There must be a principle of judgement somewhere, there must be something that decides what thoughts I will renounce, what feelings I will like, what desires I will go with, etc. There must be something that wills. This power now lies fully in the subconscious. As with Leibniz, it is a certain unconscious mingling of ‘unconscious’ perceptions, feelings, volitions, etc., that when they reach a certain threshold, make us focus on them, make us will them. This is now the principle of action. Leibniz even dreams of explaining the exact course of this mingling through calculus, much like now through brain-scans we seek to explain the exact course that leads up to our actions and convictions. Our will, becomes the result of a ‘subconscious will’, our thought, only the result of a ‘subconscious thought.’

It is not so much that after the critics of the priority of consciousness, the unconscious can be discovered. The ‘unconscious’ had always been there; as the totality of forces that lay at the root of our thoughts, feelings, and desires. It is that now we give a power that at first lay only with conscious mind —the power to decide, to act, to will, to think—, to these unconscious forces.

II. I doubt, I think

Further, with the quote in the book on Hieronymus Bosch; “what we see as the expression of the subconscious mind was for the Middle Ages the promptings of God or the Devil.”

There are then these forces, ‘unconscious’, that stem from a ‘subconscious mind’ that is much larger and much more powerful than our own conscious mind, and that influences our own conscious mind in what and how it thinks. A subconscious will, much larger and much more powerful than our own will, determining our own will. Coming from God, Leibniz or Spinoza would claim. Or, does this idea of a ‘subconscious mind’, come from the Devil? For, the idea of a ‘subconscious mind’, is not an innocent idea. We give away our freedom to these ‘unconscious processes.’ It is an idea that leads us to proclaim “I am not in control of myself, it is my subconscious ‘speaking’, ‘willing.’” What were mere forces afflicting us, on which we can deliberate, and in response to which we can freely react or not react, we now gives these forces power. And in fact, we give them our power, the power of our mind. The power to choose, that resides in ourselves, in our I, is now given over to the things that afflict us. The power to will and to think, that we only know by way of the intimate knowledge we have of it in our consciousness of ourselves, is now postulated to exist ‘subconsciously.’ The mind of consciousness, becomes dethroned by ‘subconscious mind.’ Is this possibly why one would renounce the idea of a ‘subconscious mind’?

Thoughts, feelings, desires, etc. no longer happen to me, I happen to these thoughts, feelings, desires, etc. We no longer speak of mere forces afflicting us, we speak of a ‘subconscious mind’. And what is the mind, but the power to think, to doubt, to renounce, to accept, to will, and decide? I am no longer a force that is afflicted with forces, I am a result of forces.

III. Two world-views

In postulating that the subconscious mind determines the actions of our conscious mind, it is easy to forget the most indubitable of facts; that from a reasoning that seeks out what is certain; prior to any postulation of ‘unconscious thoughts’, there is an awareness, I, mind, Cogito, that must be aware of these forces for us to speak of their existence. And this I, this I can doubt, it can will itself to not accept whatever forces seek to determine its actions. There is no ‘unconscious’, without a consciousness being aware of something and postulating that there must be an ‘unconscious’ responsible for itself.

In this idea of the subconscious mind, there is something of the Devil, in that the idea destroys our freedom.

In postulating that our consciousness is the result of unconscious thoughts, feelings, desires, etc., we forget that in certainty; thoughts, feelings, and desires, can only be said to be there because I am conscious of them. I am no longer a mind, in a position to reflect and decide on the thoughts, feelings, and desires that I am conscious of. No, this reflecting and deciding, is determined by the thoughts, feelings, and desires, of the mind that is controlling me.

We are confronted here with two radically different world-views. In the one, there is I, and I am afflicted with desires, feelings, etc. I can choose how I react to these.

In the second world-view; the choice of the I vis-à-vis its conscious thoughts, feelings, etc., is itself determined by ‘unconscious thoughts.’

How can this second world-view emerge?

By removing this essential difference between consciousness and what afflicts it, by removing the essential difference between I and what happens to I. And this can happen by taking the ‘leap’ we spoke about; by renouncing certainty, and choosing speculation.

In short, by renouncing Cartesian dualism. By renouncing the idea that the mind is better known than anything else this mind can come to know. Or, by no longer caring about what is known best, but only about what is known, however obscure it might be, however hypothetical it might be.

IV. A dangerous idea

We like to think that the history of thought is one of continuous progression and discovery. We like to think that Bosch or Descartes had not yet discovered the power of the subconscious, and this is why they believed that the unconscious powers were things that happened to us, and vis-à-vis which we enjoyed a freedom, and why they didn’t believe that our freedom, our ability to choose, is the result of these unconscious powers. But, at least for Descartes, there were good reasons for renouncing the idea that a subconscious mind is prior to our conscious mind. For, seen from an order or reasons, from the question ‘what is most certain in my experience?’, consciousness is absolutely prior to whatever unconscious forces we might postulate to be the cause of this consciousness. From the question ‘what is most certain and evident in my experience?’, freedom is absolutely prior, and the precondition for choosing any theoretical postulation.

It is only within our mind, that ‘unconscious forces’ can emerge. There are surely forces afflicting us, without our knowing, trying to control us, but to give these forces more power over us than we have over them. Why are we willing to do this? Especially if it is not based in certainty? Only we, in the intuitive knowledge that we have of our own minds, know what it is like to think, to doubt, to decide, and to will. Why would we give this power over to that ‘je ne sais quoi’ that might be at the origin of our thoughts, willings, doubts, etc.? And why, if we do so, would this make it so that our own power to think, doubt, decide, and will, must disappear?

V. Generosity, freedom

There is something of ‘the Devil’ in the idea of a subconscious mind, for it is an idea that gives us less freedom than we can have. Not because the unconscious forces trying to control us are thrown at us by the Devil, but because there is something of the Devil, in believing ourselves to be completely at the mercy of these unconscious forces.

For Descartes, the supreme virtue is generosity. We read his definition in the Passions of the Soul:

“Thus I believe that true generosity, which causes a person’s self-esteem to be as great as it may legitimately be, has only two components. The first consists in his knowing that nothing truly belongs to him but his freedom to dispose his volitions, and that he ought to be praised or blamed for no other reason than his using this freedom well or badly. The second consists in his feeling within himself a firm and constant resolution to use it well - that is, never to lack the will to undertake and carry out whatever he judges to be best. To do that is to pursue virtue in a perfect manner.” (Passions of the Soul, §153)

Generosity consists foremost in knowing that nothing truly belongs to us but the freedom to dispose our volitions. Generosity is possible, in the knowledge that we have of our own free will. Now, is there any idea that, if believed, would lead us further away from this realisation, than the idea of a subconscious mind controlling us? The idea that we are not in control? The idea of a ‘mind’, that is prior and more powerful than our own mind, and of which our mind is merely an expression, entirely passive in itself? We would no longer be created in His image, free and certain. We would only be a finished product at the end of an assembly line.

It is not that the subconscious of modern psychoanalysis would have been incomprehensible to the thinkers of earlier ages, it is that these thinkers would renounce it as a stupid and dangerous idea. A ‘subconscious mind’, a contradiction in terms, leading us to renounce our freedom, making impossible the pursuit of virtue. ’Of the Devil’, perhaps.

Concerning Descartes, Alain writes:

“Douter métaphysiquement de sa propre volonté, chose si commune, c'est exactement manquer de volonté.” (Alain, Idées).

We doubt our own will, not realizing, that this doubt is nothing but an act of our own free will. There is no out of freedom, and we circle around in it, looking for an exit that would lead us to a theoretical perspective from which we can look at freedom from above. Until we realize the impossibility of such a perspective, and we are forced to accept what we always were.

Man has the peculiar ability, to enslave himself by way of his own theoretical constructions. Perhaps, the ‘subconscious mind’, can serve as such a construction? In trying to claim a perspective not constrained by the perspective of our own mind, we seek to think about reality from the perspective of a transcendent God, but in doing so, we might be enacting the Devilish desire to renounce our own freedom, our own responsibility, and enslave ourselves. Uncertain knowledge gained, our minds lost.

Sources:

Walter S. Gibson. Hieronymus Bosch. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973.

René Descartes. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, Volume 1. Translated by J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, D. Murdoch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

G.W. Leibniz. New Essays on Human Understanding. Translated and edited by Peter Remnant, and Jonathan Bennett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Alain, Idées. Paris: Flammarion, 1983.

Michel Henry. Généalogie de la psychanalyse. Paris: PUF, 1985.

You are doing real philosophy. I wonder what are the dominating questions on your mind and how it informs this post. Is there someway to speak with you directly?