This is a text devoted to the concept to which this site owes its name: tólma. In it I touch on how for the classical Greek spirit, tólma (usually understood as boldness and audacity), is both at the origin of all evil, and an essential part of philosophy and the search for truth. I do so by way of Hesiod, Plato, and Plotinus. Tólma stands for a daring to depart from one’s lineage, Nature, and the gods, and thus for a daring to depart from oneself. It is with Hesiod’s description of “the race of iron” that this daring is identified as the root of all evil. With Plato however, there emerges a positive sense of tólma. For in testing the arguments of the great thinkers who came before, we have to dare to critique them, to see if they are worth anything, and to see if we truly understand them. Without this daring, we would never discover anything new, nor would we ever deepen our knowledge of what we already believe. Are these two senses of tólma —senseless destruction & the constructive daring of philosophy—, to be combined? I argue they are, and Plotinus offers the framework for doing so.

I. Philosophical Patricide

Today, I want to read a passage from Plato’s Sophist with you.

“Visitor: In order to defend ourselves we’re going to have to subject father Parmenides’ saying to further examination, and insist by brute force both that that which is not somehow is, and then again that that which is somehow is not.

Theaetetus: It does seem that in what we’re going to say, we’ll have to fight through that issue.

Visitor: That’s obvious even to a blind man, as they say. We’ll never be able to avoid having to make ourselves ridiculous by saying conflicting things whenever we talk about false statements and beliefs, either as copies or likenesses or imitations or appearances, or about whatever sorts of expertise there are concerning these things—unless, that is, we either refute Parmenides’ claims or else agree to accept them.

Theaetetus: That’s true.

Visitor: So that’s why we have to be bold enough to attack what our father says. Or, if fear keeps us from doing that, then we’ll have to leave it alone completely.

Theaetetus: Fear, anyway, isn’t going to stop us.”

(Plato, Sophist, 241d-242a)

I do not want to focus on what is being spoken about, but rather, about the attitude of the interlocutors. That is, not on what they have to say about Parmenides’ argument —that what is is, and what is not is not—, but about how they express their attitude towards this argument. What is this attitude? It is expressed clearly by the visitor a few lines earlier: “patricide.” In testing the veracity of Parmenides’ argument, our interlocutors express this engagement as one of patricide. As they say, “we have to be bold enough to attack what our father says.” For indeed, it takes a certain boldness, to dare to question the tried and tested beliefs of those who came before us. It is this boldness that is grasped in the concept of τόλμα (tólma), which means as much as audacity or boldness, usually in excess. The concept refers to that disposition of character that leads one to discard sound moral advice, to recklessly critique one’s ancestors, or to think one knows better than authority. It is that disposition of character, that leads one to think it is better to think by oneself, and that one doesn’t need to listen to those wise men who came before. The child that, out of youthful rebellion, renounces listening to its father, this is tólma.

Yet the significance of the concept is much broader, and refers first and foremost to one’s attitude vis-à-vis the gods and nature. To think one need not follow nature’s law, or that one knows better than nature, this is tólma. We can think of those who think that lab-grown meat is better than the real thing, those who think they should live isolated from the elements, wearing sunscreen when the slightest amount of light hits their skin, or those who think poisoning the earth’s soils will lead to anything good. This is all tólma. And as such, much of what we deem wrong in this world, is expressed in this one simple concept. But first and foremost, for our present inquiry, it is this idea of ‘patricide’, of audacity vis-à-vis one’s father, predecessors, and the gods, that is essential to grasp how the Greek spirit views evil.

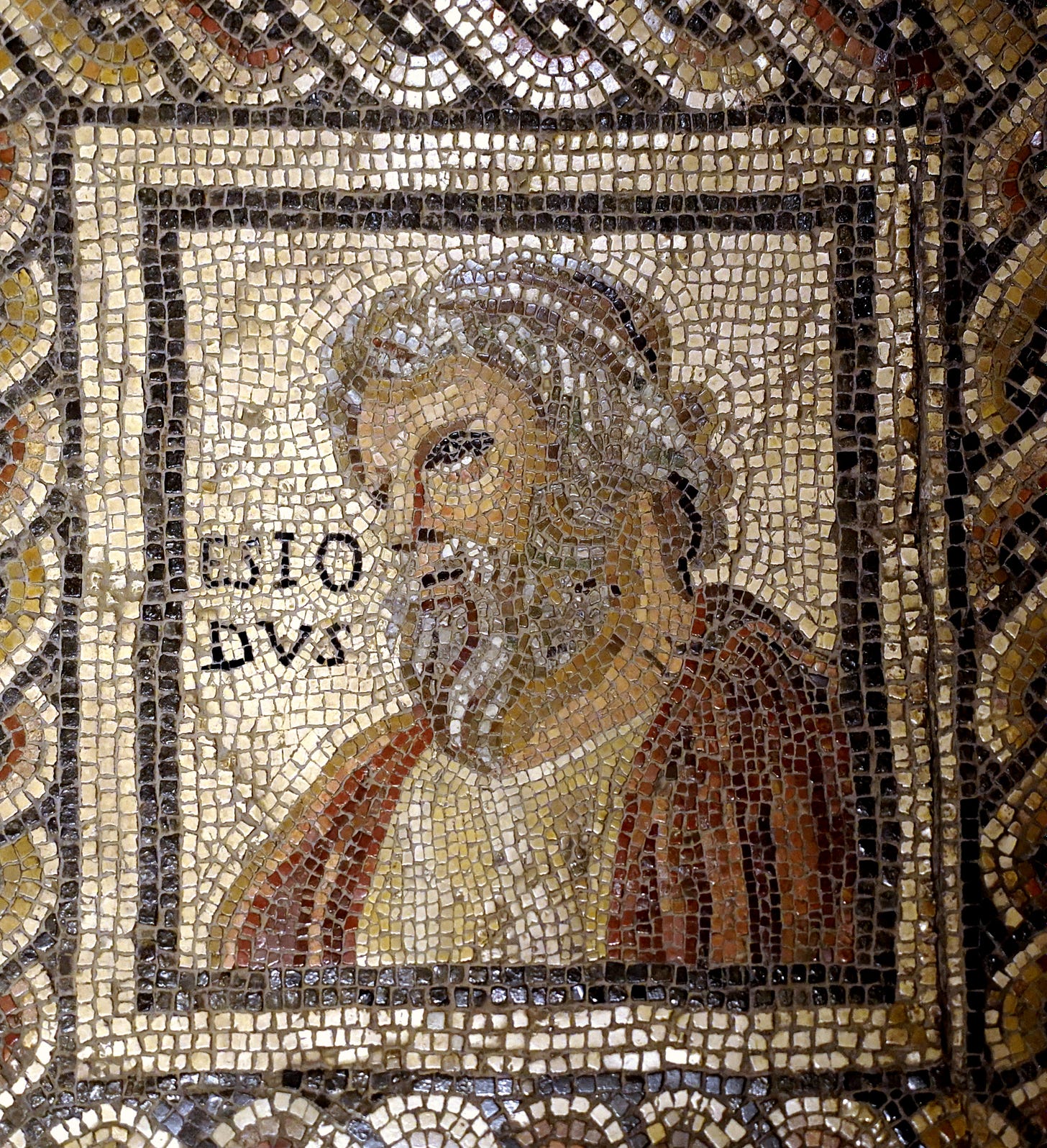

II. In ignorance of the gods’ punishment

We are familiar with Hesiod’s teaching of Ages. At first there is a Golden age, in which there is but love and harmony, until we pass into the last and worst of ages, the so called Iron Age, in which men know only corruption and strife. And after the Iron Age, it is said that the cycle starts again, for evermore. A cyclical view of time, in which paradise flows into hell, and hell flows back into paradise. In Hesiod’s description of the last age, the Iron Age, he writes about its inhabitants:

“Soon they will cease to respect their ageing parents, and will rail at them with harsh words, the ruffians, in ignorance of the gods’ punishment; nor are they likely to repay their ageing parents for their nurture.”

(Hesiod, Works and Days.)

All that is evil, is grasped in this attitude of boldness towards where one comes from: the divine, nature, one’s lineage. And it is precisely this attitude that characterizes these people as inhabitants of the Iron Age. It is a lack of respect, and a desire to get rid of one’s own origins. And thus, also a desire to get rid of oneself, for in many senses, one is one’s origins. Tólma, this audacity, it is all here in the “race of iron”.

One dares to go against what came before. But in order to do so, one has to first want to go against what came before, one has to want to depart. And why would one do such a thing, if one were not first possessed by a discontent for what came before? One despises, one even hates, what came before, and thus one dares to depart. This is the evil encapsulated in the concept of tólma, this daring to depart from one’s lineage and oneself, driven by a hatred of oneself and one’s origins.

But as the passage from The Sophist illustrates, philosophy essentially consists in an entertaining of this attitude. One has to test Parmenides’ argument, and in doing so, risk committing a form of ‘philosophical patricide’. In this passage from The Sophist, we find the entire dialectic of philosophy expressed: at once a deep respect for those wise men who came before, but at the same time, a willingness to test their arguments for ourselves. An abiding in what is known to be true, and a fearlessness, to critique this very same truth.

It is as the testing of gold. One assumes there to be gold, and it is precisely because one assumes there to be gold, that one ventures to test it. With mere dirt, one would never do such a thing. One must depart from a complete taking-as-evident, and test the argument for oneself. And in doing so, as the interlocutors of The Sophist fear, run the risk of being accused of ‘patricide’. Here we see the full and positive depth of tólma; critique, but only to deepen our recognition of the value of what is being critiqued. We are with Parmenides’ truth, believing it completely, and then we depart from it, we question it, but only to return more deeply to our original disposition. This is tólma, and it teaches us that often we have first to depart from the truth, in order to abide in it more completely. We see here clearly, how as much as tólma signifies the root of all evil and descent, it is also clearly positive. For without this willingness to depart from what is believed to be true, we would never discover anything new, and we would never deepen our knowledge past the initial phase of naive belief. It is because of this audacity to depart from what we believe to be true, that we come to see what is different from it, and come to see the effects of what is different. And in knowing horror at the results, we are led back to our initial belief, only now enriched by true knowledge.

III. The Genesis of Tólma: Plotinus

We said that tólma consists in a daring to depart from what came before, in an audacity vis-à-vis one’s lineage, and a critique of commonly accepted truth. But how exactly, does this audacity emerge? For an answer, I want to look at the magnificent opening of Plotinus’ fifth Ennead. I cite in full:

“What can it be that has brought the souls to forget the father, God, and, though members of the Divine and entirely of that world, to ignore at once themselves and It?

The evil that has overtaken them has its source in self-will, in the entry into the sphere of process, and in the primal differentiation with the desire for self ownership. They conceived a pleasure in this freedom and largely indulged their own motion; thus they were hurried down the wrong path, and in the end, drifting further and further, they came to lose even the thought of their origin in the Divine. A child wrenched young from home and brought up during many years at a distance will fail in knowledge of its father and of itself: the souls, in the same way, no longer discern either the divinity or their own nature; ignorance of their rank brings self-depreciation; they misplace their respect, honouring everything more than themselves; all their awe and admiration is for the alien, and, clinging to this, they have broken apart, as far as a soul may, and they make light of what they have deserted; their regard for the mundane and their disregard of themselves bring about their utter ignoring of the divine.”

(Plotinus, V.1.1. Mackenna translation.)

There is a double forgetting displayed in this passage; a forgetting of the Father, but also a forgetting of oneself. And the common principle of this forgetting is a “primal differentiation with the desire for self ownership.” It is with the audacity, the ‘tólma’ to depart from what one knows to be right, that all evil emerges. Because we want to be ourselves, we turn away from where we come from, and eventually, we forget where we come from. As the child brought up away from home, will fail in knowledge of its father. But Plotinus stresses, that being brought up away from home, the child will also lack in knowledge of itself. How is this possible? It is the desire for self-ownership that leads to the forgetting of one’s origins, but how could it lead to the forgetting of oneself? If we read the passage again, it is obvious that for Plotinus there is hardly any difference between forgetting of oneself, and the forgetting of one’s Divine lineage. Both amount to one and the same thing. How is this possible? In order to give an answer, we must quickly sketch a rough outline of Plotinus’ system.

In Plotinus’ vision of reality, everything starts with ‘the One.’ This ‘One’ is the supreme principle and essence of all reality; it is entirely simple and sufficient unto itself, lacking of nothing, containing no division or multiplicity, and it is even said to be beyond being. This ‘One’ is identified as the Good. Out of this first principle there emerges Nous or ‘Intellect’, and out of this Nous there emerges the World-Soul, out of which proceed various individual souls. And it is out of Soul, that matter emerges. And, matter is identified as Evil. The One is first, and Nous and Soul flow out of the One. They ‘emanate’ from the One. It is important to know that this outflowing does not happen in a temporal manner. It is not that first there is the One, and then in a second and third moment in time Nous and Soul are born. Rather, the three existents, or hypostases as they are called, co-exist in a non-temporal manner. The One inheres in Nous, and the One and Nous inhere in the Soul. Their relation is that of a circle and its essence —the centre of the circle. The One being the centre, and Nous and Soul being increasingly distant circles around this centre. In this manner, Soul and Nous are distinct from the One, but at the same time, their very essence is the One. And it is only because of the continuous presence of the One, that Soul and Nous can be said to exist.

Now, we are a soul, a particular instantiation of the one Soul, and because of the non-temporal co-existence and inherence of hypostases, our essence is the One. But, as living embodied beings, our eyes fixated on this world of matter, we are not constantly conscious of our essence. And as such, we are like the young child that Plotinus speaks about, wrenched from home, no longer conscious of our divine lineage —Nous and the One—, and thus, no longer conscious of our own essence, of our true selves. As we read,

“to find ourselves is to know our source.”

(Plotinus, VI.9.7,)

We do not know where we come from, and thus, we do not know ourselves. And it is because we do not know ourselves, that we do not know where we come from. But why, do we not know ourselves and our source? Plotinus already told us; because we turn away, because of “the primal differentiation with the desire for self ownership.” We turn away from our natural movement which is that of a circle around its centre, and choose to go our own way, in a straight movement away from our source, and thus, away from ourselves. It is this audacity, this tólma, this daring to depart from our natural movement. But why, would we dare to do so? Why would we orient ourselves fully towards matter, and lose sight of our proper origin and direction? We read again from the passage: “their regard for the mundane and their disregard of themselves bring about their utter ignoring of the divine.” This is clear, it is because we value what is foreign to our essential selves —matter—, over ourselves, that we eventually forget about our selves. We are so excessively focused on what is happening in front of our eyes, that we lose sight of the eye doing the seeing. A soul looks at the world, and so enamoured by what it sees, loses consciousness of the one doing the seeing. Plotinus says:

“Admiring pursuit of the external is a confession of inferiority; and nothing thus holding itself inferior to things that rise and perish, nothing counting itself less honourable and less enduring than all else it admires could ever form any notion of either the nature or the power of God.”

If we read this passage closely, we have our answer. We pursue things external, and thus lose sight of our Selves. But why do we pursue things external? Because we hold ourselves inferior to things that rise and perish. Because we hold our souls inferior to the material world. The pursuit of the external, is only a “confession of inferiority.” It is not entirely clear, but it seems that the disposition of inferiority precedes the pursuit of the external. This would make sense, for why would one seek anything else, if one is entirely content with oneself, what would drive one to seek anything else?

IV. Descent

From this perspective, the reason for the soul’s descent is entirely negative in motivation. It is because one is discontent with oneself, that one departs into what is foreign. One cannot bear the circling motion of one’s nature, and attempts to flee.

We do not know ourselves, nor do we know our origin. We must ask quickly, how do we come to attain knowledge in general? As any good student of philosophy knows, the attainment of wisdom is preceded by the love of wisdom, and the attainment of truth is preceded by the search for truth. Likewise, we do not know ourselves, because we have come to love what is other than ourselves, more than ourselves. We do not yearn for this knowledge of self, and are not interested in searching for it. We look outwards, because we are not interested in what is to be found inwards. This is what Plotinus is saying. Tólma, in Plotinus, this daring to gain knowledge of what is foreign, but this daring is preceded by the daring to entertain that what is foreign is more valuable than oneself. The daring to love what is foreign, more than oneself. Tólma —a failing to listen to the Delphic prescription to ‘know thyself.’ And for Plotinus this is not merely a human attitude, but the metaphysical principle responsible for emanation. As above, so below. And as we get trapped in our particular addictions because we value matter over ourselves, so Soul gets trapped in matter, because it values what is other over itself and its Divine origin. And likewise, Plotinus says it is by an act of primordial tólma, that Nous emerges from the One.

And this daring to depart, as we read, was caused by our hatred of ourselves, which makes us flee into what is foreign. But is this the only reason? For just as the passage from The Sophist showed us that there are two ways of tólma —both a senseless critique and a testing of gold—, are there not also two ways in which we depart from ourselves? One with a negative motivation, and one with a positive motivation? In the example of Plato, tólma could signify both the desire to destroy what came before, and the desire to deepen our understanding of what came before by way of thoughtful critique. Likewise, in the descent Plotinus speaks about, could there not also be two senses to tólma? To flee from ourselves, and to deepen our knowledge of ourselves? As often, we get to know our own place in the world better, when having travelled far, we return home. As it takes what is other, to more clearly see what is one’s own, as contrary is known by contrary. A reading of Plotinus would lead us to believe that this is the case. For in the Plotinian system, there is a clear function to the Soul’s descent, to the tólma of the hypostases. This emanation, this journey of the Soul out of the Good and into the Evil that is matter, it knows a purpose. For, as contrary is known by contrary, the experience of Evil leads to a clearer knowledge of what is Good, as the experience of light is the more intense, the more we were previously submerged in the dark. Furthermore, as Plotinus would affirm, not all knowing is equal. There is both intellectual intuition, and dialectical demonstration. And we might know about the reality of what is Good and Evil by demonstration, but only a very small percentage of people will be persuaded by this to prefer the Good. Most however, need the knowledge of experience, of intuition, in which there is contact between the knower and the known. And so it is with evil; most need to experience evil, before they are persuaded that the good is to be preferred, and evil to be avoided.

“Where the faculty is incapable of knowing without contact, the experience of evil brings the dearer perception of Good.” (Plotinus, IV.8.7.)

And so, it is precisely in order to attain this superior kind of knowledge —intellectual intuition—, of both good and evil, that the soul must first experience evil, before it can revert back to the Good. There is then this function to the soul’s long and painful descent into matter. For this descent is a journey of discovery, in which the soul seeks knowledge of what is other than itself, in order to be reverted back to the simplicity of self-knowledge.

V. To destroy, or to deepen

“The human soul and its limits, the scope of human inner experience to date, the heights, depths, and range of these experiences, the entire history of the soul so far and its still unexhausted possibilities: these are the predestined hunting grounds for a born psychologist and lover of the “great hunt.””

(Nietzsche, BGE, III, §45)

We ask once again, why does the soul descend into matter? tólma, is the answer. This daring to depart from one’s lineage, and from oneself. But why, does one dare to depart? To flee from oneself, or to deepen one’s self-knowledge, like the knowledge of Parmenides’ claims is deepened, by critiquing his statements? Does one critique, merely to destroy, or to deepen one’s understanding? Does one depart, merely to flee, or to deepen one’s understanding of one’s origins? When we speak of tólma, both of these senses must be kept in mind. Both the root of all evil, and the origin of self-knowledge, which is, knowledge of the Good. And as a knowledge with contact between knower and known —intuition—, is much stronger than a knowledge without such contact, the soul must experience evil, in order to gain greater clarity about the Good. An experience without which the “great hunt” for experience would remain incomplete. The vast terrain of human experience, only to be experienced by those who dare. As the Visitor says in The Sophist, “so that’s why we have to be bold enough to attack what our father says.” To experience, in order to know. To experience, in order to attain a knowledge inseparable from experience. “Fear, anyway, isn’t going to stop us.”

The question is in our attitude; how do we undertake this “great hunt”? To catch something, and nourish ourselves. Or, to merely flee from our Selves.

To be continued.

Sources:

Plato, Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper. Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997.

Hesiod, Theogony and Works and Days. Translated by M.L. West. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1999.

Plotinus, Enneads. Translated by Stephen Mackenna.

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by Judith Norman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.